The Tale of Akbar

A Fable Set in Mediaeval Iran

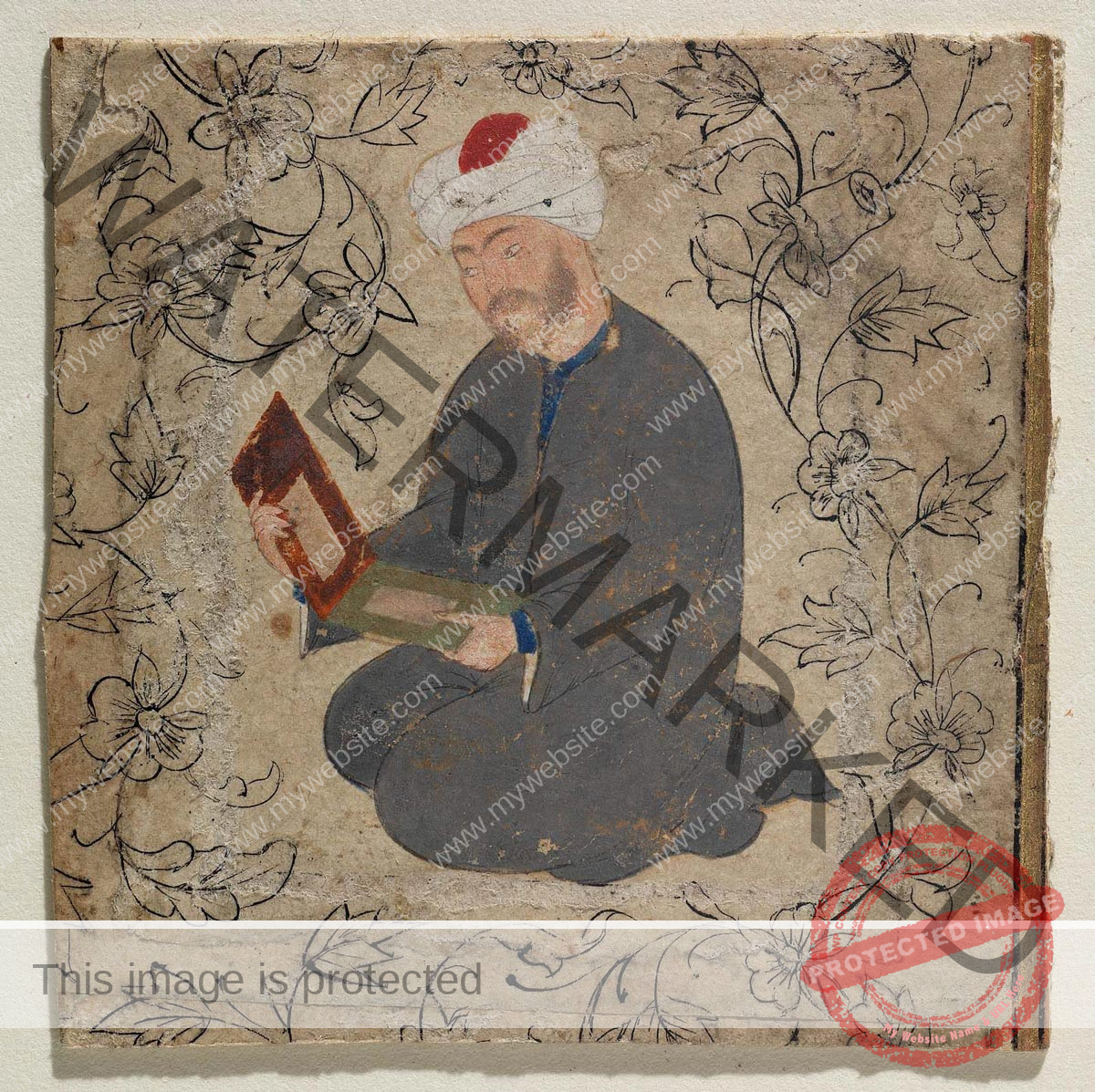

Many, many years ago I wrote a series of fables, each in the style of the country the tale was about. The purpose of this project was to make an illustrated book for the new born son of a very good friend of mine. My aim was by this means to guide him to take an interest in an ancient medium, that perhaps is one of the best ways for us to discover our common roots and the inescapable fact of our oneness as a species. If you look at stories from around the globe, you can see the clear line of oral tradition that is ample proof of the commonality of our psyche. From every part of the world come fables that illustrate the history and evolution of humankind in its perpetual struggle towards understanding its roots and its destiny. They operate as a kind of base learning medium, teaching children and grown ups anything from social etiquette to history, philosophy and morality. Below is a sample of a tale I wrote for the above collection. It was never really finished, and is of course at best only a pale imitation of the great tales it tries to emulate. But it may interest some people. This one was written in the style of old Farsi fables.

“Once upon a time, in the far and vast country of Iran, which was known to the West as Persia, in the great city of Isfahan, there was a prosperous and bustling market, which the people there about call a Bazaar.

“Once upon a time, in the far and vast country of Iran, which was known to the West as Persia, in the great city of Isfahan, there was a prosperous and bustling market, which the people there about call a Bazaar.

Now, Isfahan is known by some as the Jewel of the Desert, and that is precisely what it is. As one approaches the city limits one sees the lush and fruitful glory of Isfahan emerge, like a miracle, out of the heat and sand. To reach the city one has to cross the Bridge of Thirty Three Arches, or Siyo-se-pol, in Farsi. This bridge leads the traveller from the arid desert, over a shallow, powerful and wild river into the greenest, most beautiful city in the whole of Southern Iran. Isfahan, the seat of Ancient Kings, and a centre of much importance to the Iranian Empire, is, even to this day, also a centre for commerce.

So it is that the Bazaar in Isfahan is one of the busiest and most valuable in all Iran. And in this Bazaar was the beginning of the odd story which I am about to tell you. Where indeed can one begin? Certainly not at the beginning, that would take too long, and as any good Isfahani would quickly remind you life is too short. Ah well let’s just tell it.

If you were to walk into the central avenue of Isfahan, you’d see a very long and broad boulevard, with row upon row of trees along the central island, surrounding emerald green pools, with decorative tiles and natural fountains, which dance day and night, reflecting the bright sun light of the desert, and magnificent ancient buildings on either side. Every one of these buildings houses some kind of craft workshop and you don’t even have to walk in to see what is going on inside, because these are not ordinary shops. They have open arches in front instead of windows, and just by standing on the pavement you can watch the craftsmen do their work. Here they make everything the locals use, from pots and pans to plates and even carpets and books. You can buy everything straight from the person who made it. And every craftsman has apprentices who are usually either his own children, or the children of someone who asks the craftsman to teach his child the trade. The apprentice then learns by doing the work under supervision, until the day he becomes a master himself.

And so finally to our story, which concerns one of these very students. The name of our young student is Akbar, which in Arabic means Great, though at this time Akbar was by no means very great. In fact truth to tell, he was rather a small and delicate boy of fourteen. Akbar the son of a travelling merchant from the Northern city of Gonbad, was an unusual boy only in the sense that he was rather small for his age, otherwise there was nothing about him to make him stand out.

Akbar was apprenticed to the famous Isfahani brass and silver craftsman, Haj Ali Assadi, an important and influential man, much respected in the community. Haj Ali had taken Akbar on as a personal favour to his father, who was an old and dear friend. Indeed Akbar now actually lived with Haj Ali’s family, since his mother had died and except for his father there was no one in Isfahan to look after him, and as his father was away most of the year, trading as far as China and India.

One day, in the second year of Akbar’s apprenticeship, on a sunny and warm day, a very fat and jolly man who looked a little Mongolian, walked into the shop, and asked especially to see him. Haj Ali was a little put out by this since he vaguely thought that his position was being undermined. But nevertheless he called to Akbar, after some grumbling that he was perfectly capable of serving the gentleman himself, and withdrew far enough to be polite, but near enough to hear the conversation. The fat man looked at Akbar for a moment and then put his hand in his travelling bag and took out a small bronze box and gave it to Akbar. Then he patted the boy on his head and told him to look inside only after dark. Giving a little bow to Haj Ali he left the shop. Haj Ali was a little distant with Akbar at the best of times, but now he was distinctly ceremonious with him for the rest of the day. Finally his curiosity got the better of his sense of dignity, and he again called the rather puzzled Akbar before him. Akbar, the poor boy of course had no idea what the box contained, or who the little man was. Stranger still the fat man had whispered to him that on no account should he give the box to anyone else, and to take care not to even open it in the presence of others, no matter who they were, or how much he trusted them. Well Haj Ali asked the boy some question or other about his progress with a bowl he was making, and then then as if he’d only just remembered, he casually asked Akbar ” oh, em, by the way who was that rather rude visitor you had today?” trying not to show how interested he was, “Was he a friend of your father? I don’t recall seeing him here about before…!”

Akbar, who had always found it difficult to look at his tutor and mentor without becoming uncomfortable, mumbled that he didn’t know, as he struggled against the rising colour in his cheeks. The Haj, his desire to know by now reaching feverish heights, loomed above the little boy and frowning, puffed something about ingratitude and, as the saying goes in Iran, eating the salt and breaking the pot. Seeing that his questions wouldn’t achieve any result, he asked Akbar for the box directly. “I had” said the Haj “hoped that you would immediately bring the box to me, after all you mustn’t forget that in the absence of your father, you are answerable to me before any old stranger that comes in off the street. But now I would thank you to hand the box over to me for safe keeping” Akbar stood, his heart in his throat and his hands behind him, twisting this way and that, and did nothing to go and fetch the box. The Haj was becoming very angry by now. With some violence he took hold of Ali’s ear, and twisting it shouted ” Right you little son of a bitch, I’ve treated you better than my own children, and this is how you repay me! Just wait till tonight my boy, there is no one to look after the shop right now, lucky for you, or else I’d skin your arse for you right here…” Needless to say Akbar was crying, and thought he may just wet his pants with fear. And as if that wasn’t enough, when he went, his nose running, back to his work, he noticed that the box was gone. He looked everywhere, but there was no sign of it anywhere.

Well that night he was not allowed down to supper until he produced the infernal box, and told the Haj what the fat man had wanted, and who he was, and what he had said, and then only after Akbar had made full apologies and said he’d eat shit if he ever disobeyed the Haj again. No matter how much Akbar swore on the Koran that he didn’t know the man, or what the box contained, or where it was now, Haj Ali simply would not believe him, and the more he cried the worse the situation got. In the end the Haj dragged Akbar to his room, beat the daylights out of him, locked the door and ordered that no one, but no one was to see him or talk to him or take him food, until he told the truth, or died, which ever came first. Akbar meanwhile cried and screamed and beat his head with his fists, trying to figure a way out of this awful mess.

At about midnight, Akbar, who had finally collapsed into an uneasy sleep, was awakened by the sound of steps coming toward his temporary cell. His whole body quaked with almost uncontrollable terror, and he was sure his end had come. The door was flung open and light poured in, framing the fat outline of the Haj. At first Akbar dared not look at his tormentor, but as the Haj spoke Akbar’s limbs began to thaw out and relax. Haj Ali was speaking, if not kindly, at least not as though he was about to tear him to shreds. In fact Akbar noted a slightly apologetic tone in his master’s voice. As he looked up he was surprised to see the look of worry in Haj Ali’s face.

The Haj, like all men of his kind, was very obsessed with his own importance, and felt that everyone should always give in to him, after all was he not rich and powerful, and did his money not give him great authority. But, as is also the way with such men, he never risked anything, especially his own skin. He would sell his own mother to avoid the minimum of pain and discomfort. So it was that as soon as his anger had subsided, he remembered that important as he was, Akbar’s father, due to return soon, was much more powerfully built that he, the Haj was rich. After all, on his travels he was constantly fighting bandits and mercenaries and so would have no hesitation in ripping him to pieces as soon as he found out what the Haj had done to his precious, and only child. So it was, and Akbar understood in the midst of all his confusion, why it was that the Haj had had a sudden attack of remorse.

At this realisation, the boy, who was older and a little larger than when we started this tale, gave a great shout of relief. Charging headlong for the Haj, he knocked the great man down on his fat arse and made his oil lamp go over. As fire broke out everywhere, Akbar turned back from his wild run, and pulled the Haj to the safety of the washing pool in the middle of the garden. There he threw the old man into the water, and laughing for the first time in many years, shouted at his master “You fat, stinking son of a whore, you are not worth even killing, so I’m just going to leave you there, I’d like to remember you just like you are now. Don’t be surprised if you never see me again, I’m going where donkeys like you can’t touch me”

With that Akbar ran out of the courtyard, onto the first mule he could find, and rode hard out of Isfahan, over the Siyo-se-pol and into the West. Under a starry clear sky, which is such a beautiful speciality of the desert, and towards the Zagros mountains on the Western border of the Iranian heartland.

Do I hear some of you asking how I know all this? Well Akbar met up with a man known as Vali Mirza Khan, a fierce and very famous bandit, who also happens to be one of my ancestors. And the story of Akbar is one that every child in my family grew up with. What, I hear some of you ask, became of our little hero?

Why, he grew up to become the famous mountain outlaw, Akbar Khan, the scourge of rich and useless merchants and noblemen. Akbar who was never caught, but died at a very old age, amongst his beloved band of fighters, undefeated and never again fooled by the surface appearance of things.”