UTOPIA vs. DYSTOPIA

When I was a kid, our idea of the future city was formed on the back of futuristic novels, movies, cartoons, articles in the media. It went something like this. In the future all things would be better, brighter, shinier. Life would be easier, leisure time would form 90 or even 100% of our daily lives since machines will perform all the tasks that thus far had been relegated to human workers. Everyone will have a flying car, a house full of robotic utility personnel, power and energy would be virtually without cost. Cities will cover most of the planet, our foodstuffs would be nutritious, abundant and most of all synthetic. We would be more or less masters of the universe and the planet will not need to provide us with resources at all since we would be empowered to cater all our needs with our wonderful and incredible machinery. Also we would by about 2010 have started colonising other planets.

So much for the utopian idea, the optimistic view of the possibilities of science and technology. The flip side was also amply illustrated and described by the very same media. So the dystopic view went the other way. It took many different forms (I remember reading Isaac Asimov’s brilliant book “A Choice of Catastrophes” back in the 70’s where he listed a catalogue of things that could end life on earth, from a scientific point of view).

The popular media and literature was also littered with tales of destruction and annihilation. Aside from the usual nuclear holocaust/the big rock from outer space/the dying sun/the collision with alien visitors of vast and malevolent superiority, there were myriad other ideas about the future that were frankly terrifying. Worldwide conspiracies by power crazed dictators, some sort of Über Hitler or Stalin that would take the world by the scruff of the neck and enslave us all, or brain-washing states that would use laser technology or some such nonsense to make us into slaves. Oh there were of course, colourful and quite often swashbuckling heroes too who would fight against the tyranny and save the world.

The one really noticeable thread in much of this kind of story telling was the finale in the countryside. Somehow when all the drama and tragic fighting was over and done with the few lucky ones remaining would invariably abandon the city and go back to the country to kick start the human race again from a more sane and manageable base.

Strangely enough quite often the two supposedly opposing views of the future, no matter how much they diverged often ended with the same conclusions. If, the idea went, we manage to survive in the long term it will be rooted in a return to the earth, to the natural world. Now this idea was nothing new in itself. Since the first murmurings of the industrial revolution, there were intellectuals and artists who made dire warnings about the dangers of leaving our fate in the hands of heartless industrialists and their diabolical, infernal machines. The Romantic movement was deeply rooted in this reaction against the industrialisation of Europe. But progress, as a scientist once aptly described, is like a snowball rolling down a mountain side and we are caught inside it. It grows with or without our intervention, it seems to have an evolutionary life of its own and we can either choose to go with it, or try, if we can, to step out of it. There is no third way. Certainly it is a truism to say that you cannot un-know something once it is known. Our dilemma is that we are most of us; at least I can say this about my generation; completely schizophrenic about the whole thing. Look at us, most of us are now deeply entangled in the bowels of technology. Computers have indeed taken us over pretty much entirely. Our whole working and leisure life is now digital for the most part.

I was listening to James Burke; the great British science commentator and writer; describing our near future as being completely electronically based and that with the growth of nano-technology and cloud platforms we would kind of become biologically enjoined to our technology to the point where organic and digital life-forms would become indistinguishable and basically a new life form. Well I am not sure that is exactly fair to what he was trying to say, but in essence that was his observation. But the most interesting observation he made was that since the circumstances of the industrial revolution are no longer valid or relevant, the paradigm that has formed to replace them is the new technology that drives everything in our world. We know, we can see amply demonstrated, that manufacturing in the industrial revolution sense has in some ways become a dinosaur and no longer relevant. The western world has pretty much abandoned what used to be the beating heart of industrial development, in the sense that the old, smelly, noisy, soul destroying factories of the turn of the Twentieth Century have become something very different, with automation and computerisation the old science fiction projections have come to be. Certainly this is true of the West. The Third World will probably dispute this, “Au contraire” they would say, “come over here to our side of the world and see how the blackened cities and industrial exploitation of the Victorian era have simply shifted in geography”. But even there sooner rather than later things will go in the direction that they have in the First World (sorry I’m old enough not to like the hypocrisy of calling it the developed and developing worlds, what arrant nonsense).

We in the fortunate West who find it rather wonderful that we recycle and we have environmental consciousness, that we are doing our bit to save the planet, resolutely refuse to acknowledge the precarious nature of our existence in the present and certainly its complete uncertainty for the future. Most of us, no matter how much we believe and talk about moderating our lifestyle, I think, would not be able or willing to give up even the smallest degree of our accustomed comforts for the sake of the Earth. It is almost a cliché that we like to think of ourselves as responsible and deep thinking about the well-being of our planet and that we are acting responsibly towards it. But almost everything we do is no more than empty gesture, tokenism to make us feel better about continuing to consume at an unbelievable scale and vast, criminal wastefulness. Indeed we are happy to apply the most meagre of band-aids to a gaping, sucking wound of our own making.

Anyway I stray from my initial point. In the last few decades we have started to see the deep, chasmic cracks that have appeared in the skin of the notion of continuing the city dwelling paradigm as a future possibility. The chaos of the present financial crisis has been, in my opinion, only the latest in a series of indicators that the city as a viable entity is doomed. Way back in the 70’s talking to my architect uncle, I asked him “How do architectural thinkers see the future of the city?”. His answer was probably one of the key things that changed me personally in my thinking for ever. He said (and I vaguely quote, I was only 15 then, so forgive me for not remembering the exact words) “Well the city will not continue to be sustainable as it gets ever bigger. The only logical safe future is the dissolution of the megalopolis back into small self-sufficient village like communities, living independently and with a more modest expectation for material goods…” A perfect analysis in my opinion.

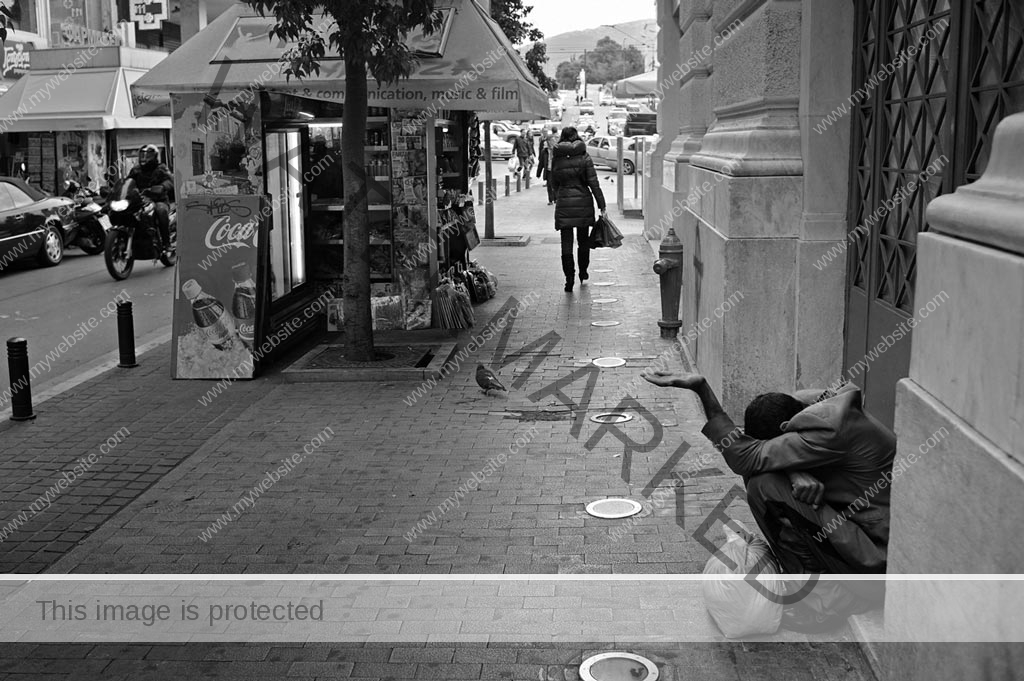

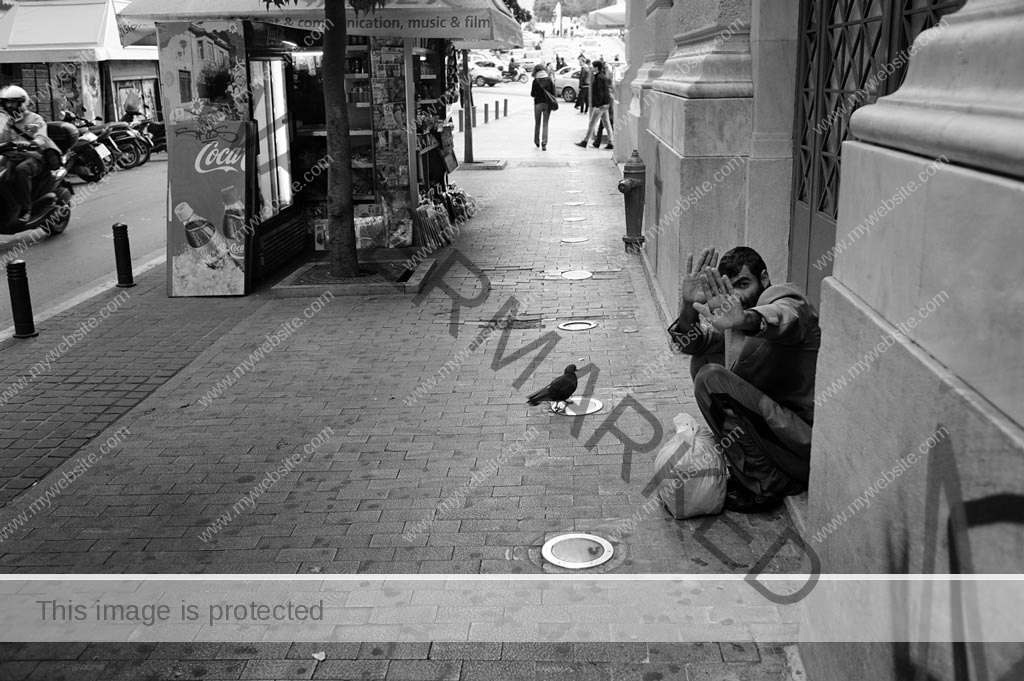

Scenes from the city of Athens over the last few years.

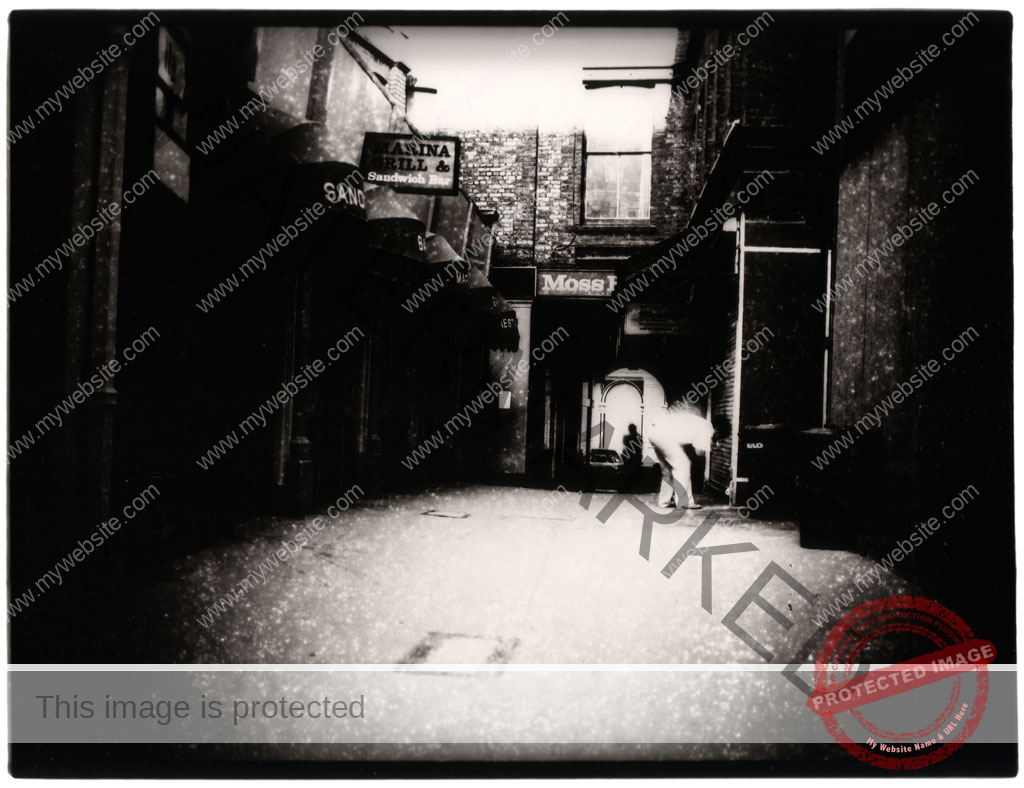

So, long way around but I get there eventually. This is the background to several projects I have done over the years. The longest lasting and most rewarding set so far is my “Invisible Cities” set which I started one fine day back in 1982 in Hastings, England when I suddenly had a revelation. It went something like this. I was walking around the town centre which, as is the depressing case of Britain, is uniformly indistinguishable at street level from every other city and town in England, when I looked up. Now remember Hastings is a historical city, one of the oldest settlements on the Island. What I saw up there, above the street level of uniform post-seventies architectural “modernisations“, was a treasure house of history. They never rose far above ground level in their meddling with plate glass and steel in most cases in the cities and towns. Above that level the architecture was like a timeline of the towns development. There was Elizabethan, Jacobean, Georgian, Victorian and all points in between to be seen, in some cases even Norman buildings. An amazing cornucopia of superb historical architecture that was somehow ignored by city developers. This was the beginning of my city series. The first series was called “Up“, obviously referring to the notion of simply looking above ones eye-line to see the various riches on display up there.

The second and perhaps longest lasting of the city series was the aforementioned “Invisible Cities” inspired by Italo Calvino’s novel of the same name, which sent me back out to search out the treasures of London and other cities I lived in or travelled to.

So finally to this present “August in Athens | Disappearing City” project. Here I was fascinated, amongst other things, by the sudden emptiness of the city as its citizens upped and left it at this time of year, every year without fail. Visiting Athens from Frankfurt for the first time, my cousin’s response to the question “What do you think of Athens?” will always stay with me. He said immediately “I don’t like it. It’s an unloved city. No one living here seems to care the least about it”. And what can I say? I love Athens, I love the feel of the city, that’s why after all I have chosen to live here for the last twenty years. But I see his point. It is true. A major characteristic of Athens is that you practically never meet anyone who would admit to being an Athenian. Almost 80% of the people who were born and are resident here still consider themselves outsiders, they still see themselves as citizens of their villages, or perhaps rather the village where their grand or even great grand parents came from.

This perhaps is the over-riding reason why Athens gives off this strong sense of chaotic unkemptness. You clearly feel when you go through town that there is a certain lack of commitment to being what it is. A city like London, or for god’s sake even LA, feels like a city, like a homogenous place, albeit the individual character of each area may well be distinct, it still presents itself as a single entity. Not Athens. This city, surprisingly given its longevity, exudes an air of being somehow temporary, somehow rootless. It feels mostly as if it were a collection of shanties that sprang up around the original core, and somehow metastasised, coalesced into a pantomime of a city. Yet you can still find so many areas that are truly urban, truly city-like.

Anyway I stray again. My point is that in the narrowest confines of the project at hand I wanted to find a way to show the abandonment of the city by its denizens.

Melbourne, Australia, © 2011.

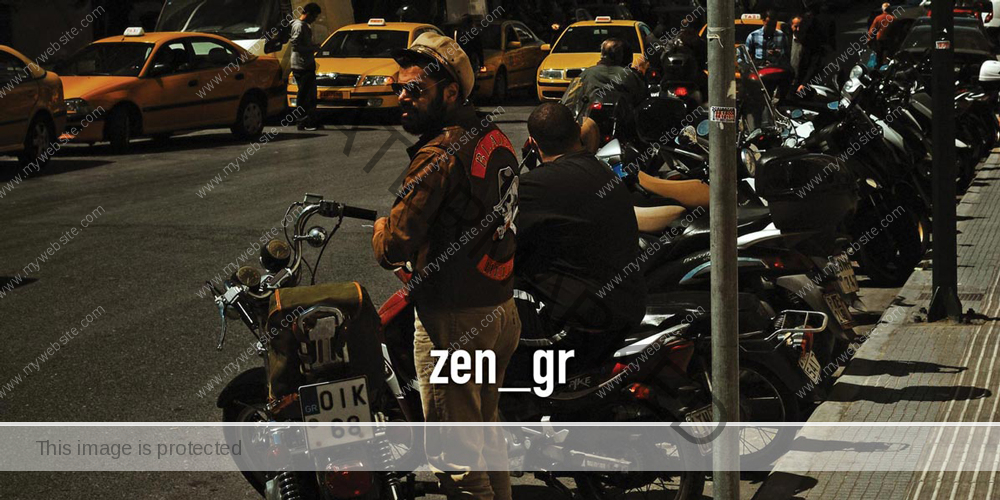

Another of my City sets, well actually two “zen_gr | Resting Places” © 2010-2014

Another obsession, this time with central market places in every town I visit, time and inclination, not to mention city ordinances permitting.

Athens Central Meat, Fish and Vegetable Market. © 2011.

The “Disappearing Athens” set, days one and two 2014