What is Straight Photography?

I suppose as good a start as any is to simply copy/paste what the almighty Wiki has to say about this “movement”.

Pure photography or straight photography refers to photography that attempts to depict a scene as realistically and objectively as permitted by the medium, renouncing the use of manipulation. The West Coast Photographic Movement is best known for the use of this style.

Founded in 1932, Group f/64 who championed purist photography, had this to say:

Pure photography is defined as possessing no qualities of technique, composition or idea, derivative of any other art form.

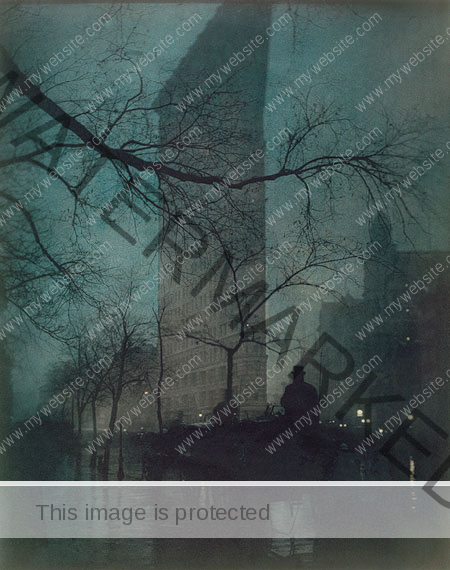

The term emerged in the 1880s to mean simply an un-manipulated photographic print, in opposition to the composite prints of Henry Peach Robinson or the soft focus painterly images of some Pictorialist photographers. At first, straight photography was a viable choice within pictorialism, as, for example, the work of Henry Frederick Evans. Paul Strand’s 1917 characterisation of his work as “absolute unqualified objectivity” described a change in the meaning of the term. It came to imply a specific aesthetic typified by higher contrast, sharper focus, aversion to cropping, and emphasis on the underlying abstract geometric structure of subjects. Some photographers began to identify these formal elements as a language for translating metaphysical or spiritual dimensions into visual terms.

This aesthetic caught on in the early 1930s and found its most notable use in what came to be known as The West Coast Photographic Movement. Photographic superstars including Ansel Adams, Edward Weston his son Brett Weston, Dody Weston Thompson and Berenice Abbott are considered innovators and practitioners of this style. Many other well known artists of this time considered themselves practitioners of this West Coast counter-culture and even formed a group known as Group f/64 to highlight their efforts and set themselves apart from the East Coast Pictorialism movement.

This emphasis on the straight silver print dominated modernist photographic aesthetics into the 1970s. Its also a type of picture that has no side effect but tell the truth in general.

It’s a nice little potted attempt at describing the idea behind Straight Photography. Although the notion that photographs can ever tell the truth, purely, is from the start an impossibility. The fact is that the moment you select, frame and photograph something you have already changed the way people will look at it and, more importantly you have made something new and special from the original object/subject.

A Little Aside

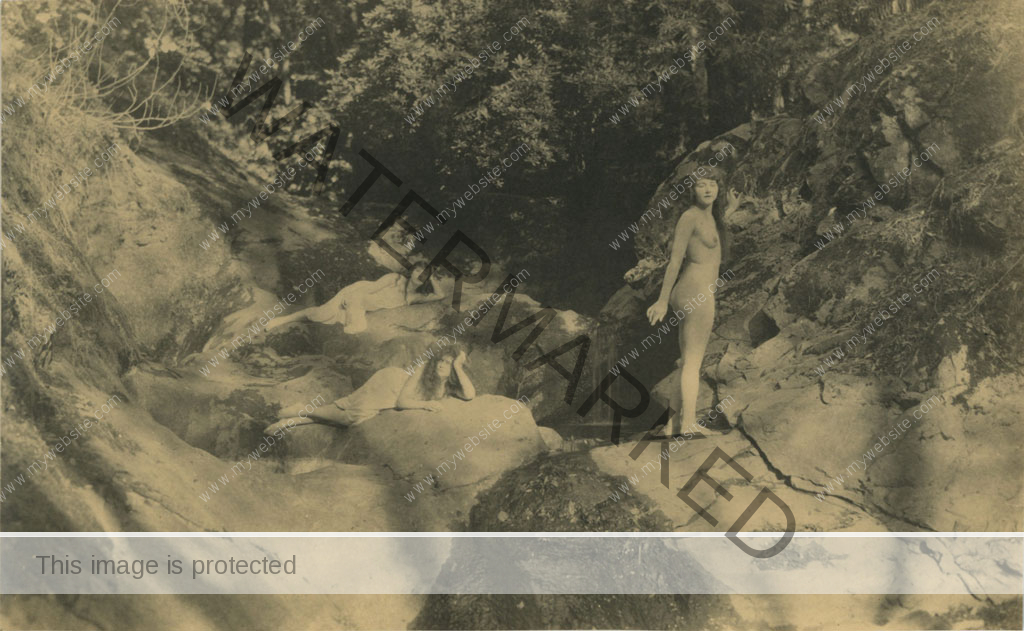

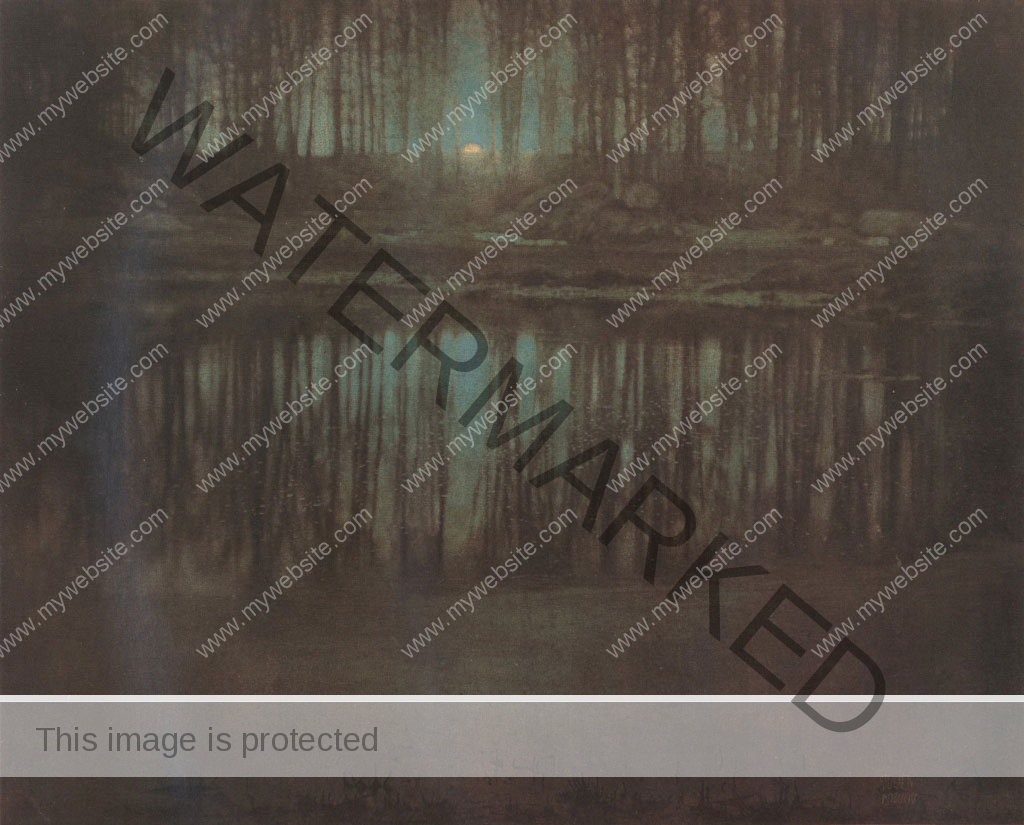

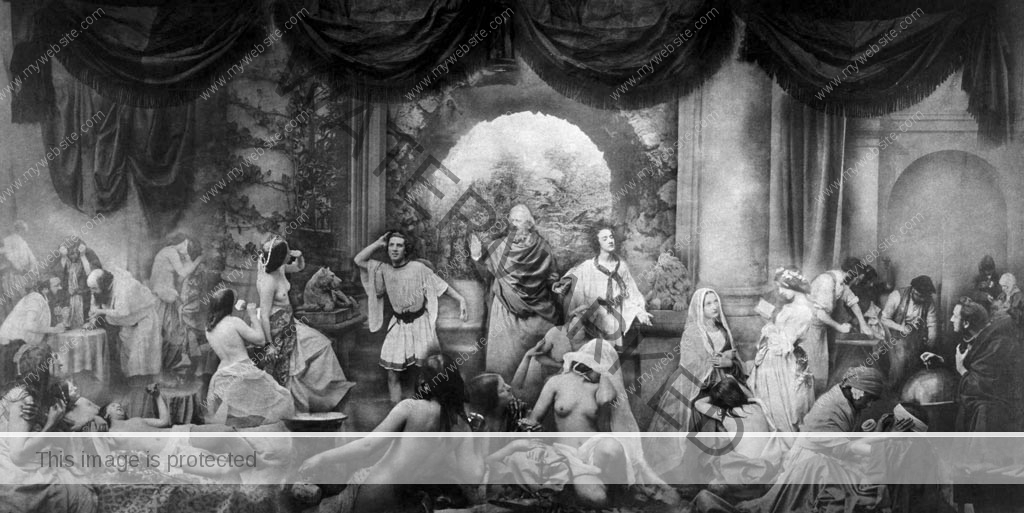

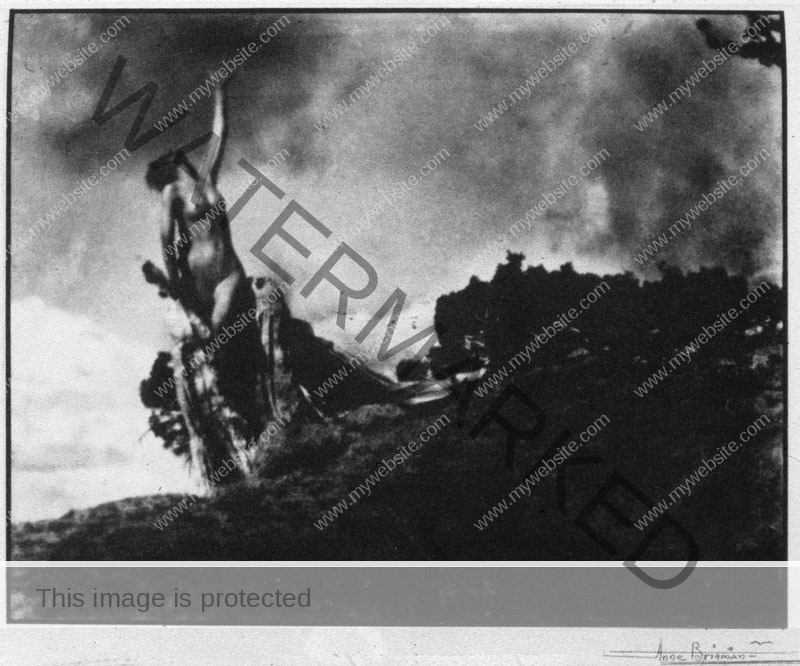

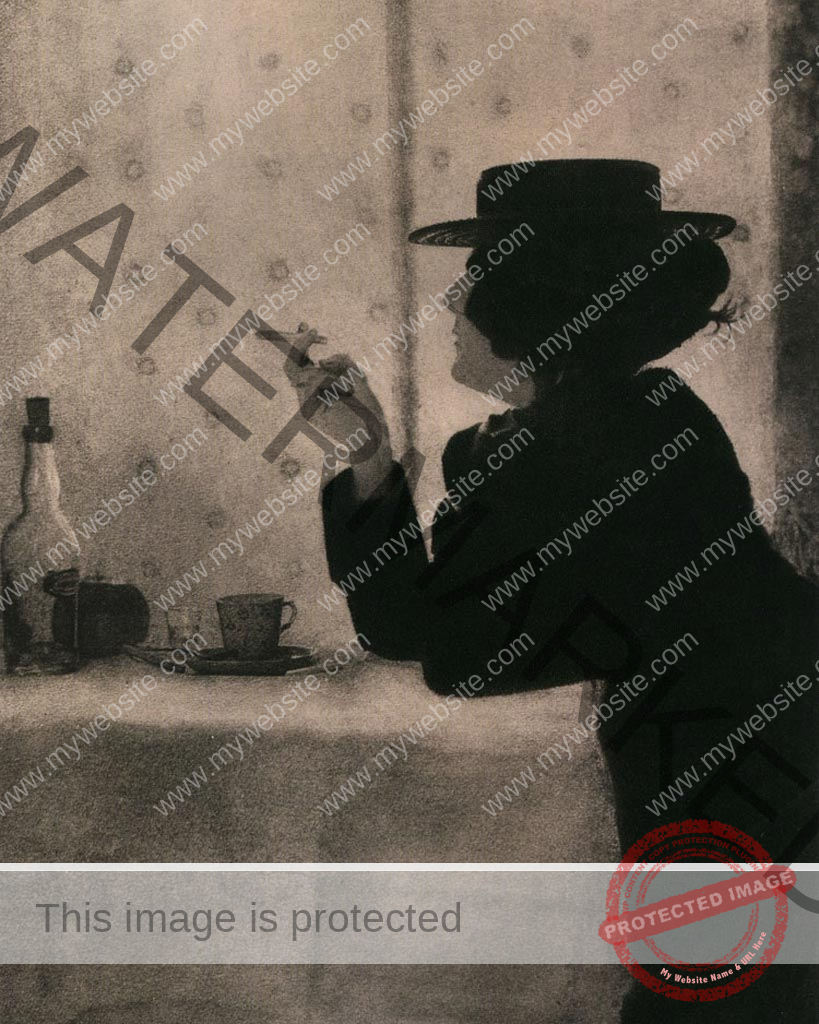

Pictorialism was a dominant force in photography in the latter part of the 19th and early 20th Centuries. The urge to create little allegories and scenarios to add substance to photographs is for me a clear indication of the ambivalence of artists and society towards photography. Pictorialist attempts at creating photographs that were set up meticulously, presented in heavily manipulated prints were the very thing that the Straight photographers were reacting against. It would, in my opinion, be wrong to think that the straight photographs were so diametrically opposite the work of this genre.

I have maintained this for years but I do not believe it to be possible to take a photograph that does not have at least a trace of manipulation, since the medium itself is a grand form of manipulation.

A few notable Pictorialists

In a sense the background to this urge to loftiness lies with the stigma that was attached to photography, its status as the poor relation of painting; when it came to accepting it as an “ART” independent from other visual disciplines. Since those early days at the end of the Nineteenth and the beginning of the Twentieth Centuries things have changed markedly in the fortunes of the two major visual arts.

What often gets lost in the discussion is that one of the key reasons why photographs felt forced to emulate painting was the love affair of Academies with painting as the king, queen and prince of the realm of visual art. There was I suspect a hard commercial reason for photographers and early experimenters to try and ape painting in order to validate their work. It may also be true that originally photography presented those with less talent in painting with an opportunity to pursue a visual arts career. Even as late as the Eighties one of my tutors at college, a painter, snorted his derision for my decision to switch to photography, accusing me of opting for a mere technical medium as opposed to the lofty heights of paint and canvas. His attitude baffled me but it also made me laugh. I thought even then “Wow, how narrow minded even these Ivory Tower artists and thinkers can be!”.

When photographers finally shook off the chains of academic strictures they broke the iron hold that golden section and other painterly notions had on photography. The photographers that took a stand and stated that photography needed to create and establish its own aesthetic, independent of pictorial constraints, of mythology, allegory and so on were making a huge leap into the Modern era. In fact it can be justifiably argued that their stance against the traditions of academic norm paved the way for modern art. Somehow when photographers stopped and looked at the medium and saw that it was powerful and valid in its own right, they also freed painting. I think a very strong case has already been made for the contribution this break with painting made to the birth of Impressionism and Cubism to name but two key movements. I think it would be safe to say that the paintings of say Degas or Renoir were heavily informed and enriched by the photographic aesthetic.

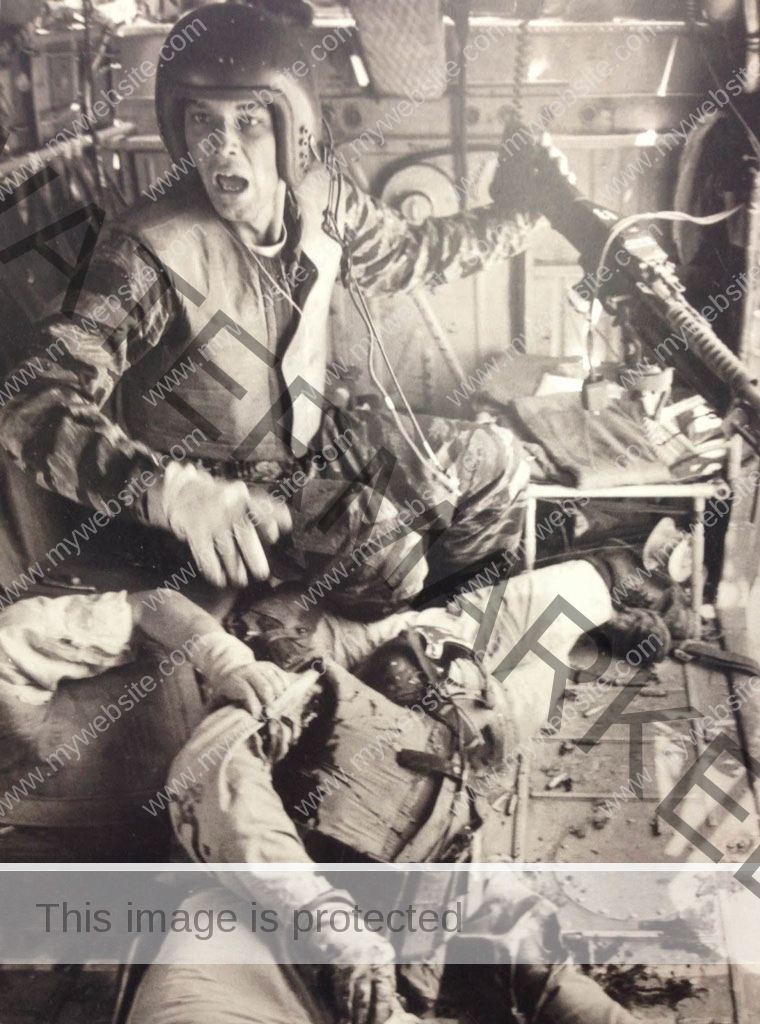

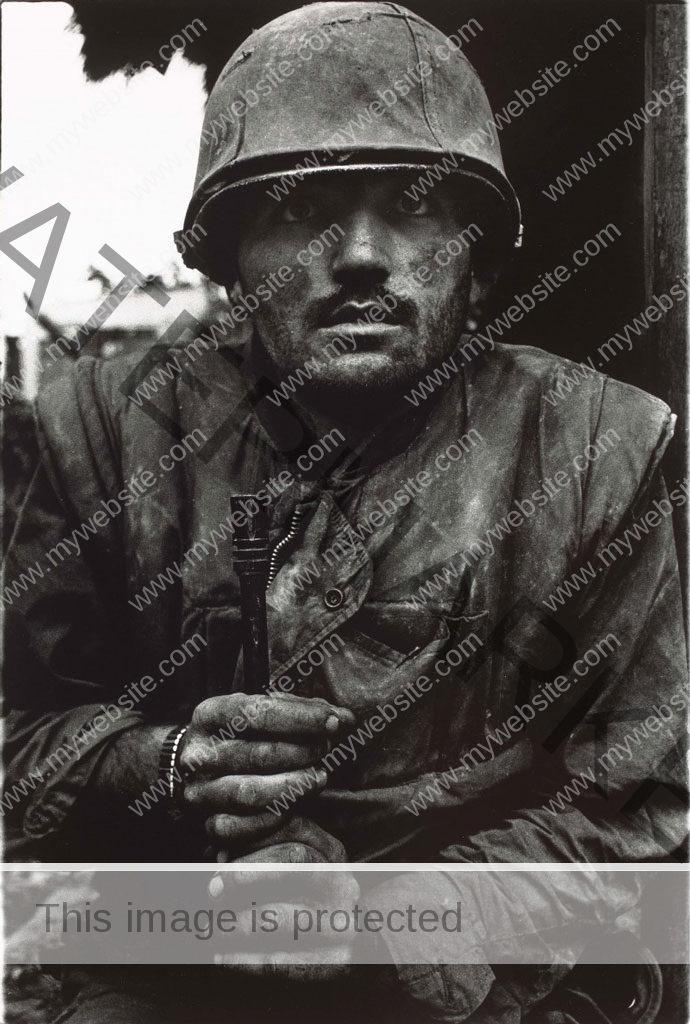

It is important to mention that the fact that the baton for realism was passed on to photography freed painting to experiment and reinvent itself. It is logical really if you think about it. After all photography is the supreme representational medium. Once pure or straight photography became more or less the established; and as technology in lens, film and paper manufacture rapidly improved; photographers like the great Erich Salomon began work that would define photojournalism. Of course there are much older photographers, as far back as the 1860’s and the American Civil War that could be credited with establishing documentary photographs as the most vital leader of the whole field. Andrew Russell, Mathew Brady and many others, working with huge plate glass cameras, covered the horror of that war in ways that forever changed our thinking about photography. Not just war photography but all photography. Ground-breaking is a phrase that is sorely overused, but it really does apply to their work. Their images, though still rather restrained in comparison to say the photographs of the Vietnam war, were visceral and filled with horror. I’m sure if Brady had had a Pentax SLR with a super fast lens and 36 frames of film he would have produced very similar photographs to those of say Don McCullin, Larry Burrows or Tim Page.

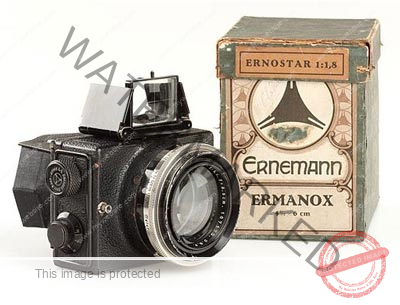

Hard Hard Reality

The major difference with the early 20th century photographers was as much a result of technological developments as of a need to establish a photographic aesthetic. For instance when Erich Salomon started using fast films and the compact Ermanox viewfinder cameras that had just come out in 1924, with its ability to shoot in dim light, he created a paradigm shift in the way we take photographs. It is not necessary to know him or his work, his influence is still with us.

Most importantly though what, for me, defines Straight Photography is that it can not, must not and will not pretend to be something other than what it is. Photography is defined clearly by its name. Composed of two separate Greek root words “Photo” meaning Light and “Graphia”, Writing or Recording. A straight photograph attempts to capture what the lens is pointed at without artifice. Its job is to record what it sees. But here is where in a sense the photographer interrupts this “purity” because consciously or not we frame, we compose, in other words, we impose order on the thing we claim to record.

This, to me is not a flaw or a falsehood. It is the lifeblood of photography. It is what defines it, this imposition of viewpoint. This is what gives every great photograph its distinguishing mark, its style. It is the very essence of the power and relevance of photography. These images encapsulate a commitment to telling the truth and at the same time elevating the mundane, humdrum, everyday to something much much deeper and more meaningful, universal, iconic.

The discourse that each photograph can potentially become is, for me, one of the essential forms of communication in existence. It can encompass in one single image so many ideas, references, philosophies – it can, in short, have transformative powers over the way we view the world of the everyday by showing us a glimpse of the exceptional.

The First True Masters

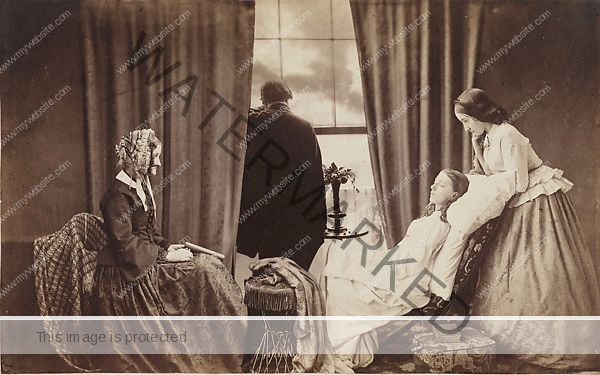

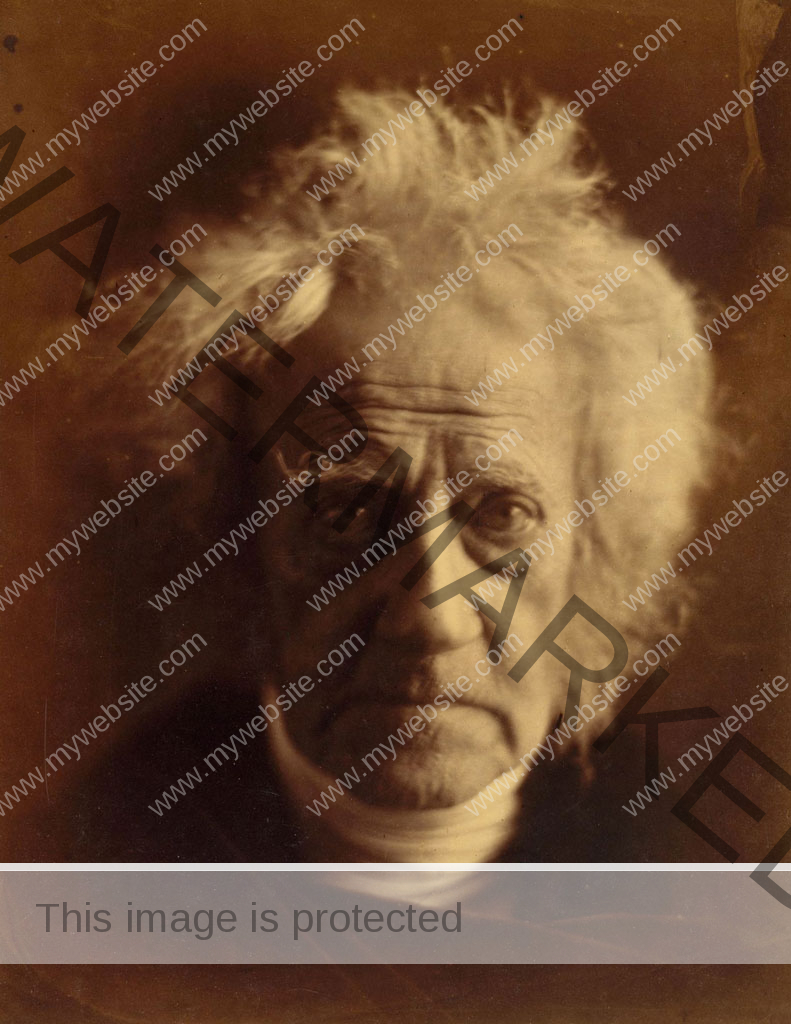

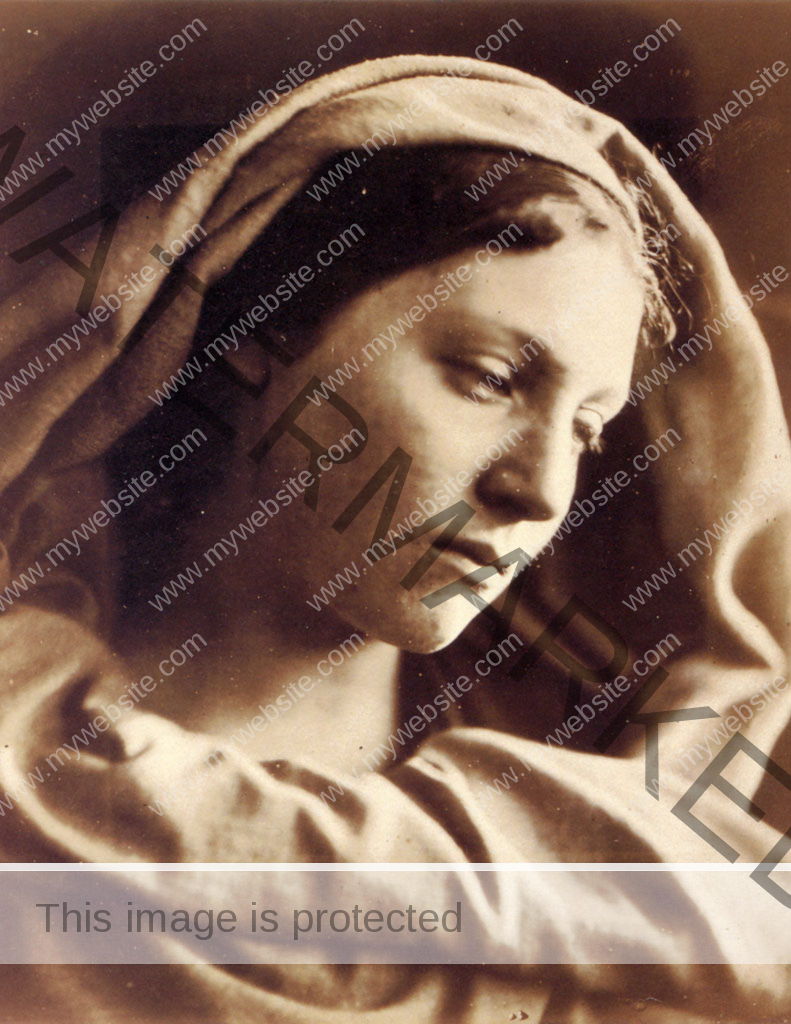

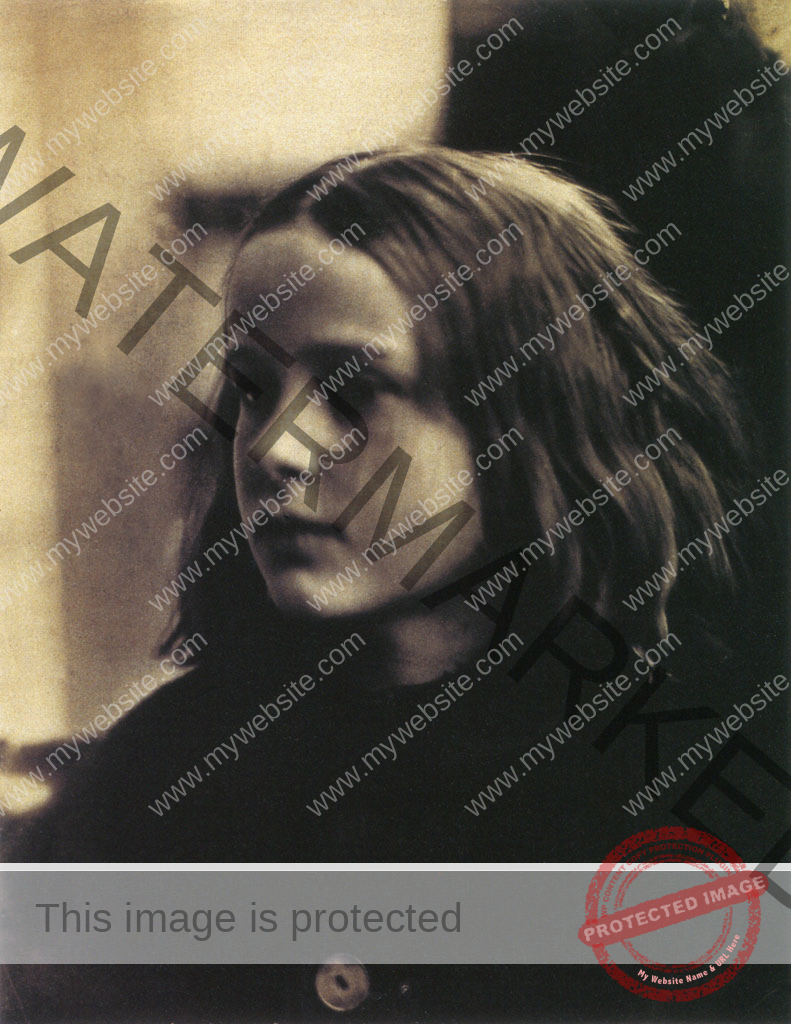

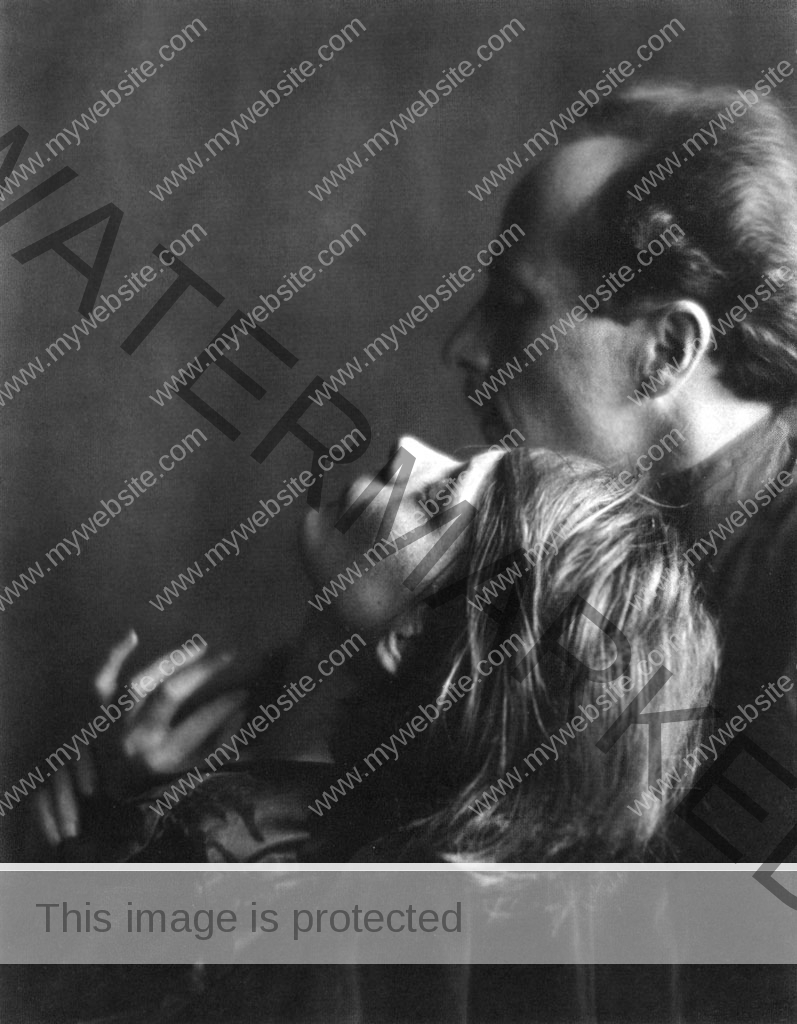

Julia Margaret Cameron (1815 – 1879)

“In these pictures all that is good about photography has been neglected, and the shortcomings of the art are prominently exhibited,” reported The Photographic Journal in an 1864 article about Julia Margaret Cameron’s “out-of-focus portraits” of the leading poets and scientists of her age. “We are sorry to have to speak thus severely on the works of a lady, but we feel compelled to do so in the interest of the art.”

… Rather than trying to suppress the chemical and physical limitations of 19th century photography, Cameron flaunted them.

Imagine this about perhaps the greatest portrait photographer of the Victorian era… This is the kind of nonsense photographers had to face from the talking heads of the academic bent!

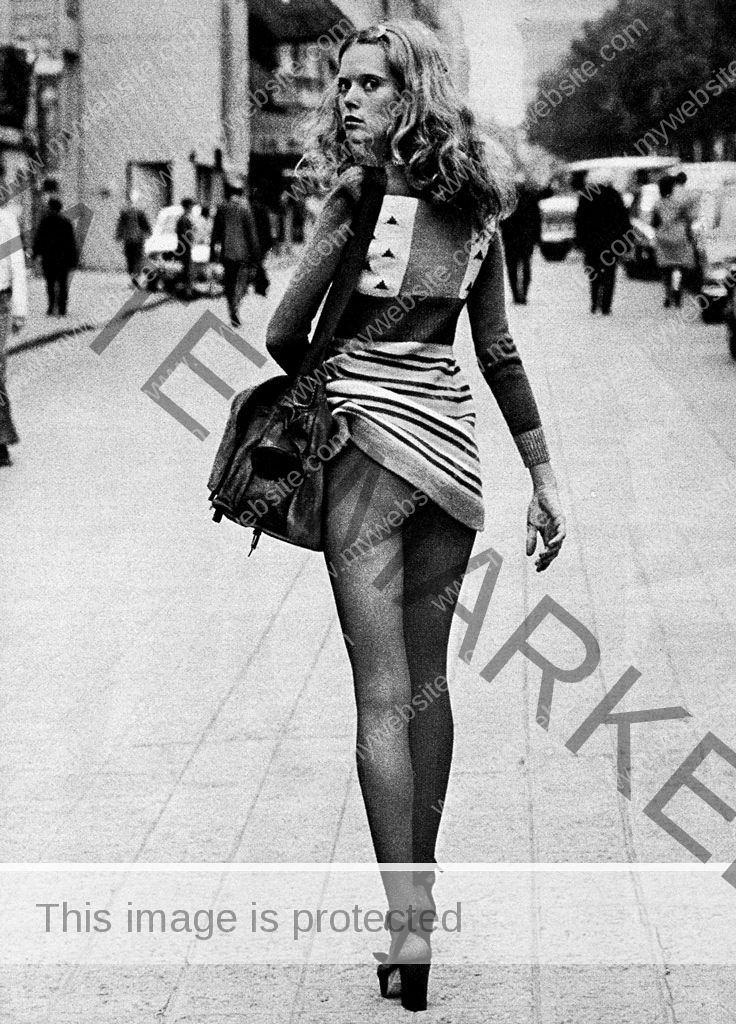

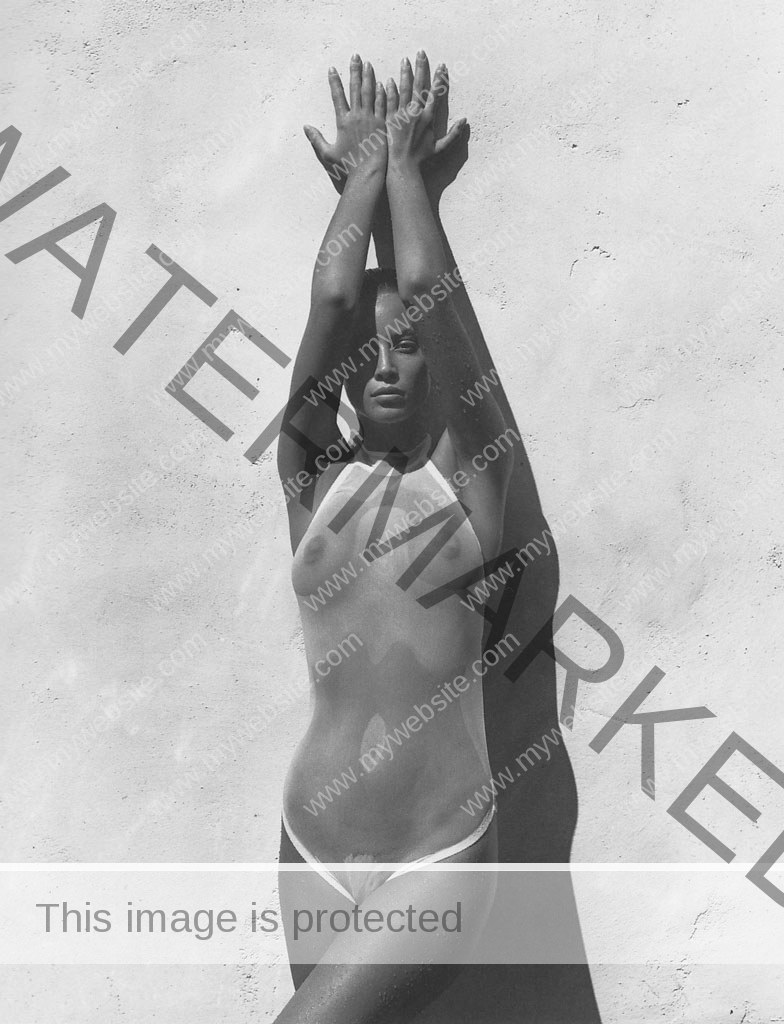

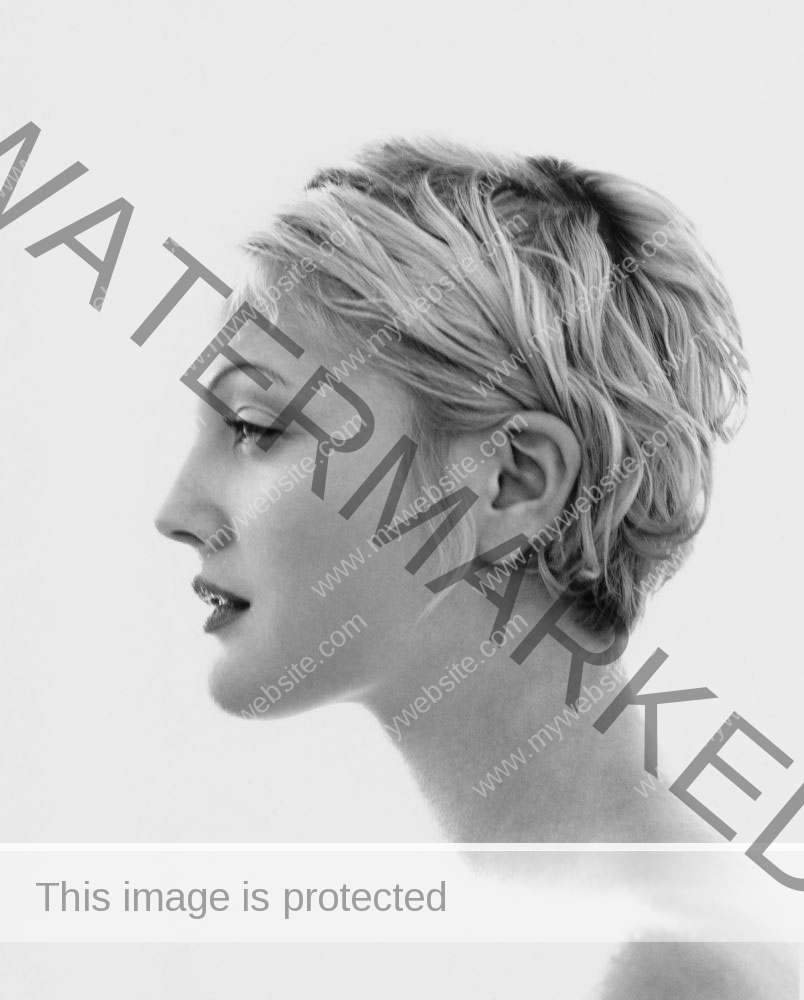

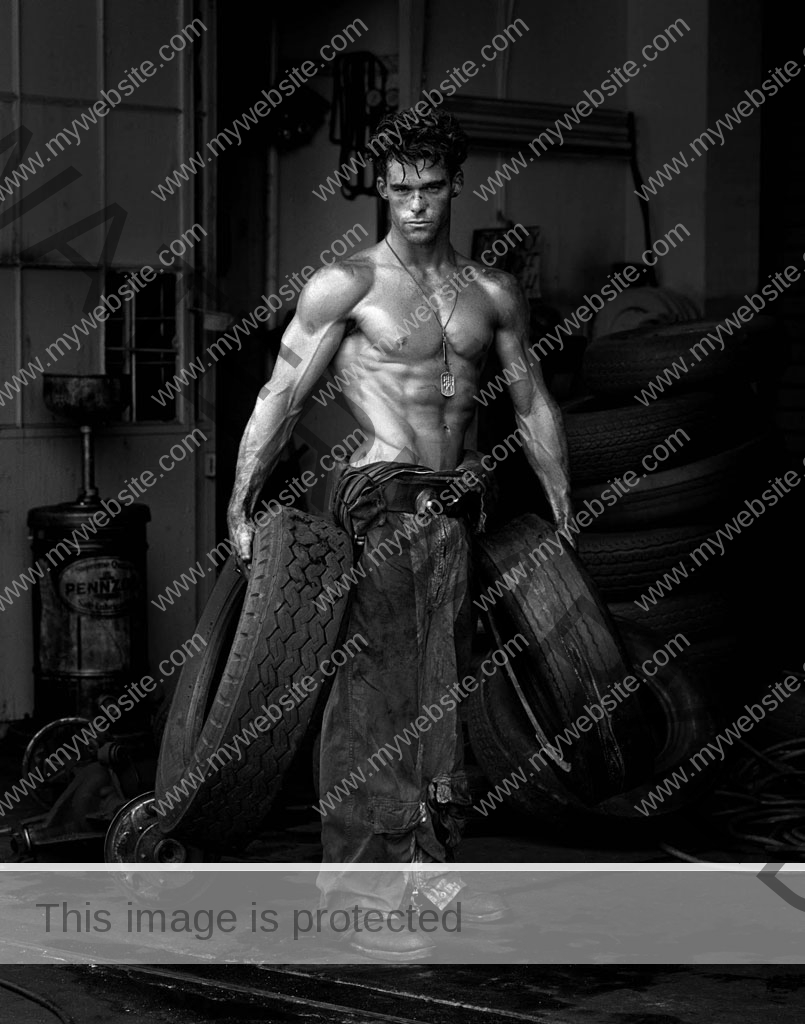

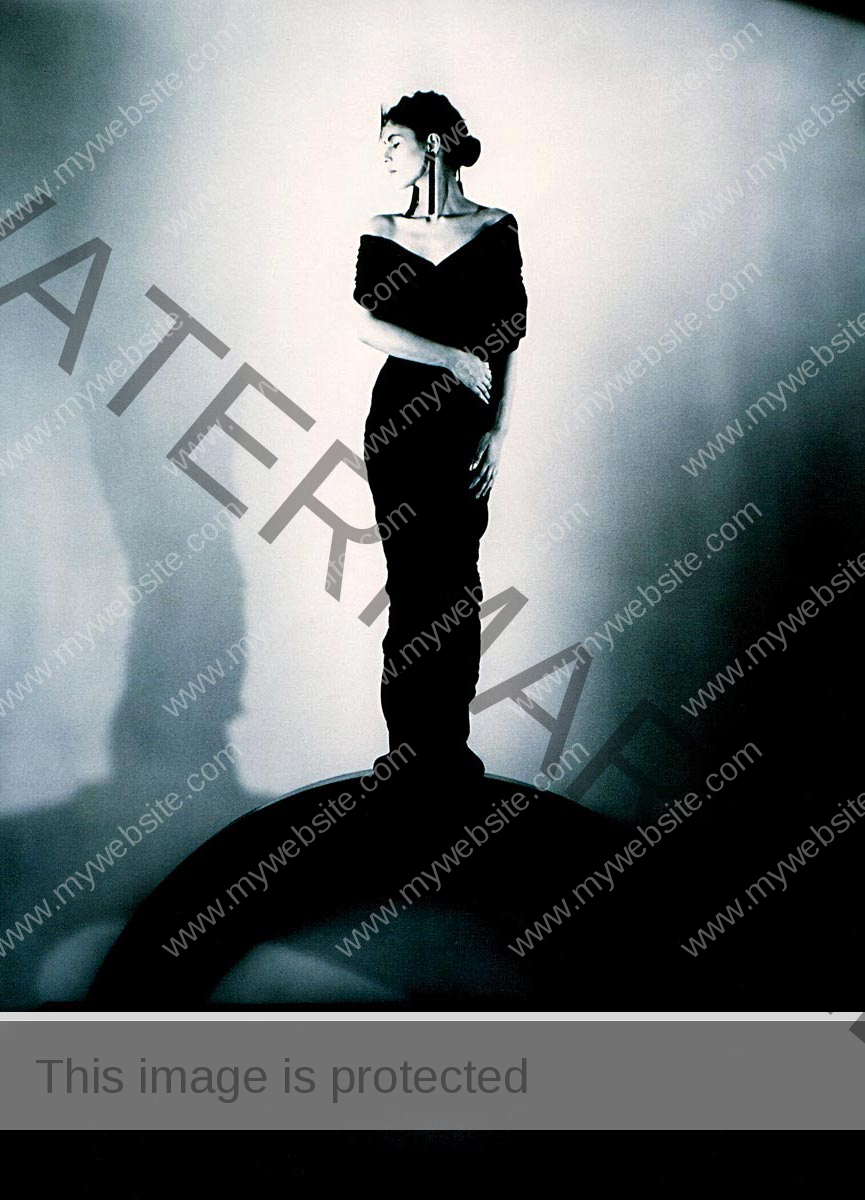

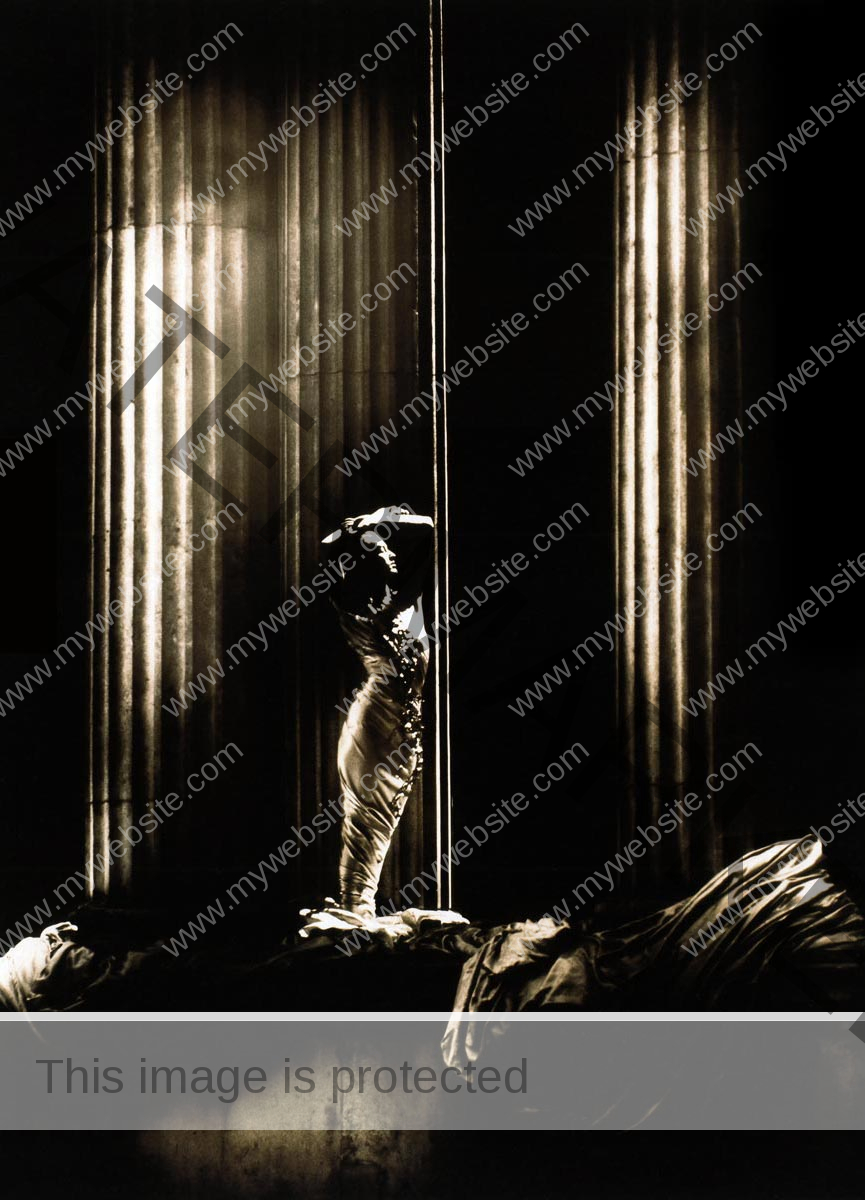

Herb Ritts (Pictorialist or Straight Photographer?)

I could go on and on. I could keep adding more great images.

But since this site is essentially where I talk about my work I guess I ought to add a few of my own images!

I think these six images kind of cover both types of photography discussed on this page.

You could say the top row is about hard reality, photographed with as little artifice as possible.

While the bottom three are clearly Pictorialist in nature. A fully stylised form.

In a way my object in writing and posting to this site is at one level also a sort of search for my place in the history of photography. By talking about it in a concrete way, placing myself as a photographer in the larger frame of “Photography” I am somehow attempting to pinpoint my own work and methodology. I think it is the only way to discover your own position as a practitioner; this holding up your work next to the images that inspired you to become a photographer to begin with.

I think that the philosophy of straight photography forms the backbone of every single photograph we see today, from the work of master photographers all the way down to the most flippant mobile phone selfie. It may be that even the majority of today’s professional photographers are completely unaware of this key period in the history of photography, but none can deny the massive debt they owe to this pioneering notion. I imagine that if one were to describe it to most people today they would be pretty unimpressed, after all the idea is so deeply ingrained in the whole fibre of photography that it is almost invisible. Of course photography is a thing in its own right with its own set of rules and parameters. Of course it is not a cheap form of painting. Not so long ago there was no “of course” to it. Whole generations of photographers had to struggle to prove that photography is a valid form of visual communication on its own terms.

So what can be said in conclusion?

I suppose I am concerned with the power of photographs, to record, to explore, to remember, to enlighten, to entertain, to educate and perhaps most importantly to communicate the sense of uniqueness in every passing moment. If we were to take time to be linear and inexorably moving forward, then photographs are one of our vital tools for capturing and preserving infinitesimally thin slices of time. I would argue in at least one key sense that all of our artistic efforts are in large part rooted in this drive to preserve, this archiving of our short lives, this leaving behind of time capsules.