The Weight Of History

In a way every photograph is a reflection of another that pre-dates it. In a very definite way no one is free of photographic influence. But as in all things certain ways of looking speak directly to each of us in a different way. And that is an essential charm of photography.

I discovered photography as a serious art around the age of twenty. I had been preparing for studying fine art and specifically illustration, having early on realised that though I was technically a competent painter, I had no talent for it whatever; frankly no matter how much I loved paintings by others, I had no drive to paint at all. I had in 1980 actually started a course in illustration at college level having been reasonably successful in the field already since the age of seventeen. It was at college while studying a foundation course in preparation for a degree in fine arts that I came across Cartier Bresson, Lartigue, Weston, Stieglitz, Alvarez Bravo, Imogen Cunningham, Steichen and many of the other early inventors of modern photography. Perhaps it is no accident that the large proportion of these Europeans found their eye in the new world. But America at the turn of the Twentieth century was the natural bastion of modern art, in fact the bastion of all things modern. It represented energy, dynamism, thrusting towards the bright shining future that was the certain destiny of this new world. This wasn’t just some theoretical philosophy, this was a firmly held belief and driving force in the young nation. Nothing new was to be excluded. And even as late as the 1980s just looking at the photography of Europeans moving over to America was energising and powerful. The sense of adventure and the discovery of totally new forms was overpowering. Think of a Swiss photographer like Robert Frank, travelling the eternal highways of the continent to discover his eye, just moving around that vastness changed his vision in the most remarkable and fundamental ways. The almost primitive power of Alvarez Bravo’s photographs, the way Stieglitz changed from a stuffy middle European into a dynamic impactful maker of images. I could go on and on; and on. My personal favourites were Jacques Henri Lartigue, Marc Riboud, Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Edward Steichen… and a few others such as Imogen Cunningham, or Dorothea Lange; whose simple, almost snapshot approach carried within it such incredible humanity, power and energy. But most of all what took my breath away was what light did to a strip of celluloid coated in silver. Light that shimmered and sang with highlights and shadows that were more seductive than any reality could ever be.

I became enchanted by what this thing could do to the world, how it could translate the most insignificant, transient sliver of a second into something majestic and rich. To look at the parochial portraits of August Sander and see the pure humanity of the work, the lack of flash and artifice that infected the late Seventies, with all the new emulsions, the high contrast, plastic papers. The work of the early 20th century led me to a new way of looking at photographs, and through them at the world out there. The greatest thing it taught me though was a commitment to what fascinated me. Although I loved doing theatrically set up work with fashion and commercial photographs, it was in portrait work and street photography that I really found the irresistible draw of the lens. I simply lived and breathed photography for the next decade or so. The darkroom became my home, chemistry so long put aside because of the dull way it was taught at school, suddenly became a vital and vibrant science of function and necessity. I think I learned more chemistry in two days of darkroom work than I did in all the years of school. Suddenly through photography mathematics and physics made sense, became essential tools to get to what I wanted to show the world. And what a rich resource it is to mine. Photography can show the world in ways that nothing else can match.

I can empathise fully with the basic tenets of Group f/64 which stated their intent to “…define photography as an art form by a simple and direct presentation through purely photographic methods”. It is perhaps the height of what can be achieved with the camera. To understand and apply the strength of the technical aspects of photography to produce what it does best, in place of its doomed attempts at aping painting. It is understood by all serious photographers that you can not separate the art from the technology when it comes to photography. In recent decades the shift to the digital formats has demonstrated that most eloquently.

But in the end, as in most technical procedures what the audience receives is the end result. The viewer may well be completely ignorant of the process and therefore enjoy the photograph in a very different way from that which a photographer or an expert would.

At university I was, reputedly, instrumental in reviving old processes and techniques and one of the first to break with the contemporary fashions of that time to seek out older and more, in my opinion, substantial techniques of earlier eras of photography. This led me to study lighting and darkroom techniques from the first half of the 20th Century and to an extent master them. My return to fibre based bromide papers and slow films in as large a format as I could get my hands on was regarded little short of retro revolutionary by my college. But study them I did. I was fortunate enough to have access to an ageing Eastern European darkroom technician who guided me through the bewildering and mostly deadly chemicals with which to work, and I learned. While other fellow students were out clubbing I was in the darkroom mixing noxious chemicals and pouring them unto prints to see what effects I could achieve. Putting film and paper through chemical torture was an incredible voyage of discovery and revelation.

Let me also explain that due to economic necessity I abandoned photography for almost a decade until 2007. At least the practice of it, though I never ceased to think of myself as anything other than a photographer. I went through a period of something akin to mourning, over the fact that all the technical knowledge and chemical know how that I had built up over the years were now suddenly and rudely redundant and that I was once more a novice, at least technically. My good fortune was that I was at least as expert in digital visual techniques through my work in graphics for the last fifteen or more years, so adapting to the digital form was less of a strain and shock than it would otherwise have been. But once I managed to get hold of my first digital camera I very quickly started working again. Allowing for the time it took to adjust my technique from film and especially black & white, and away from darkroom based photography to Photoshop, I was soon photographing at an ever intensifying pace. Losing my job as an art director and graphic designer and becoming unemployed led to me having a lot of time on my hands to devote to photography again. After a period of fumbling with the new parameters of the digital imaging world, I was soon thinking about working on a project that was substantial enough to inspire me to work seriously in the field again.

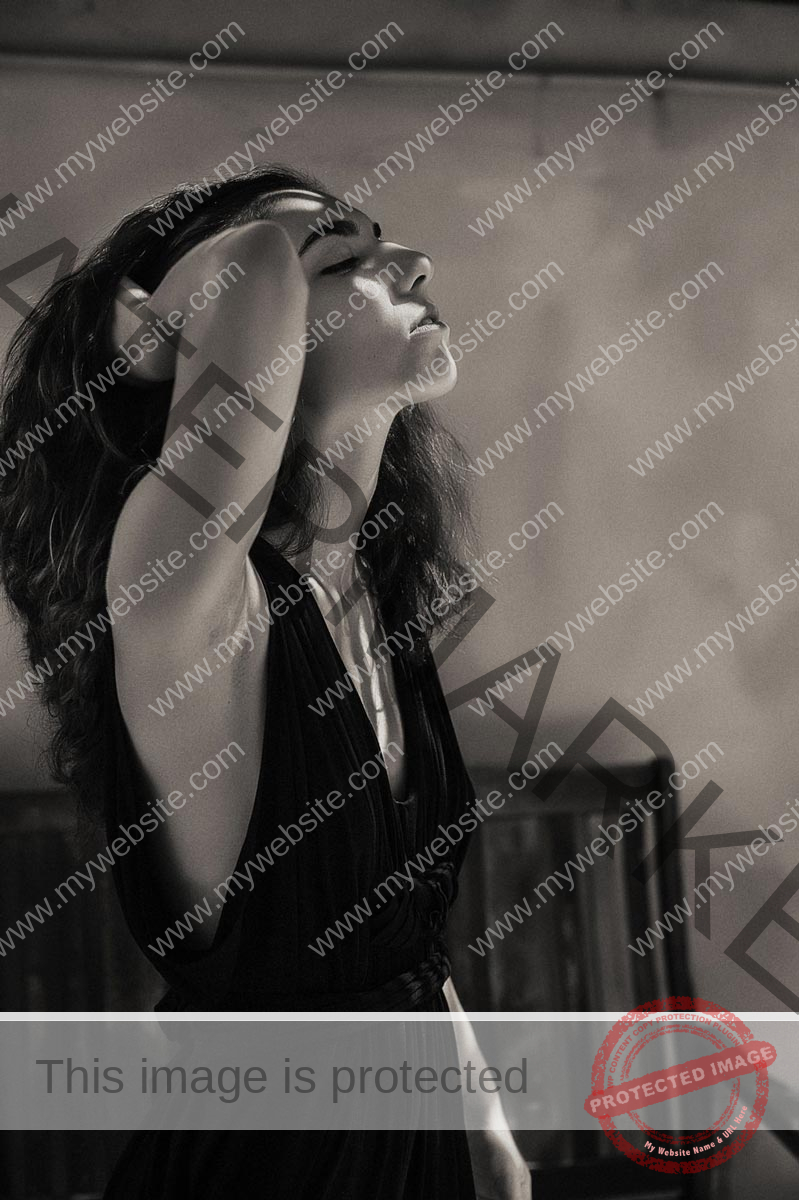

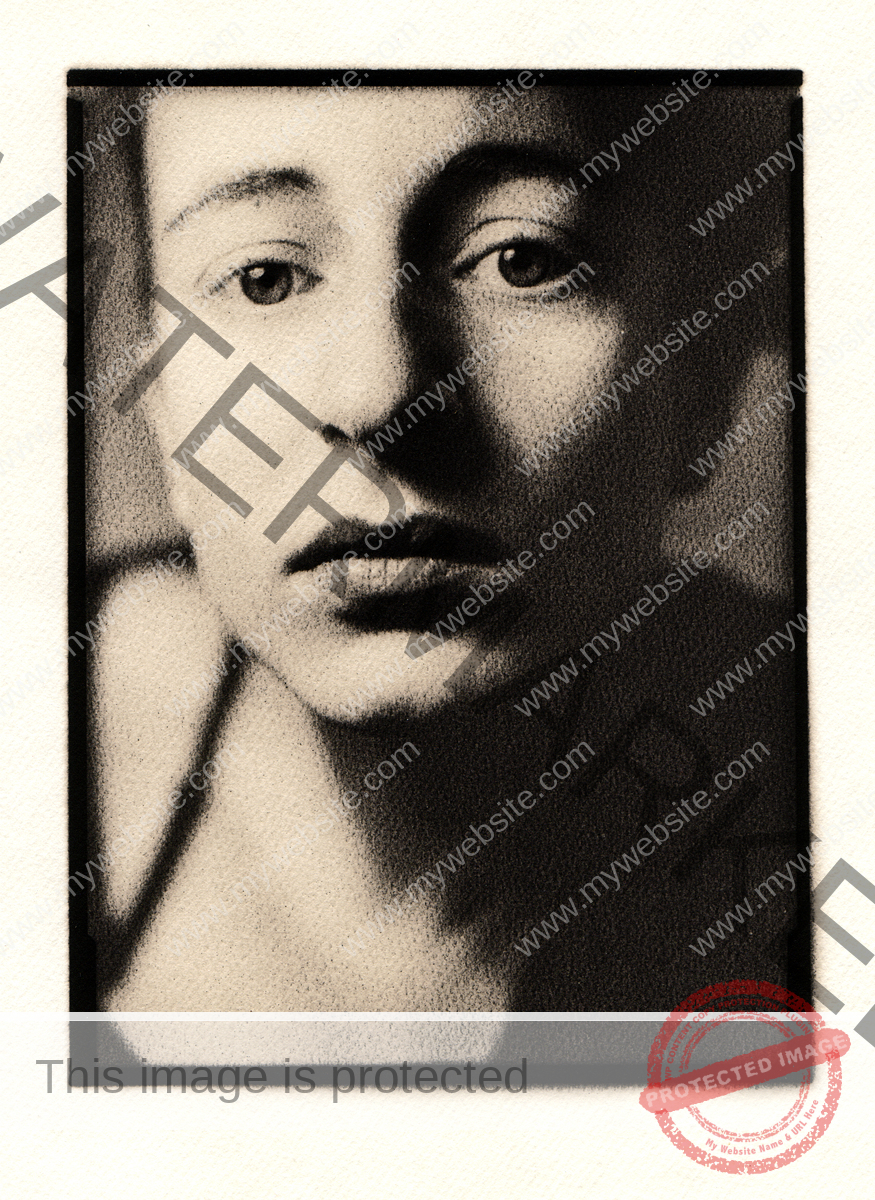

But I stray. I simply wanted to discuss briefly what I have been noticing about my own work. Lately in putting together a massive series of photographs that I have been shooting over the last two years or so (end of 2011-2014 at the time of writing) I have been overwhelmed by how many references to older work there are in my recent photographs. I titled this project “Woman • Movie Star • Icon”. A self-explanatory title I imagine.

Looking at this work and where my instinct wants to take it in post process has been a wonderfully educational experience. With my above mentioned project I wanted to break the bounds of digital photographs and take the results back a little, perhaps a touch of my old inclination to be a retro revolutionary? All I can say is that several old tendencies began to become obvious as I enlarged this project. My original thought was to keep the images very much contemporary in technical terms, in other words not try to give the feel and aesthetic of digital a total shove in favour of older film techniques. In the end though the urge to enhance the images to have more of a film feel became too overpowering to resist. Almost at the end of the shooting part of the series, over two years into the project, I finally changed my mind about how I was going to show the work. And now have set myself the task of working backwards on the sets to produce a new group of final images. God help me.

Vishy Moghan 03.06.2014

All photos are from the series WOMAN • MOVIE STAR • ICON. © 2011-2014