…Yet Another Thing

Oh yes. There is another contemporary problem that photography and photographers face. And it baffles me.

We have it seems become totally enamoured with speed. In line with the “modern” era’s ever increasing acceleration we have come to expect all things to be done faster. When I first started studying photography in 1980 we were already in the grip of looking for ever faster films and papers, rapid development chemicals, flash bang and wallop. I was one of the first of my generation of students as far back as 1980 in fact to go directly from plastic papers to pinhole cameras. I very quickly found our high speed equipment and films a little lacklustre and more than a little irritating. I kept looking at the photographs that had originally attracted me to the whole thing and I felt that something really important and completely essential was missing from what I was doing and not just, it was missing from almost all contemporary photographs. Something a little richer, deeper. I could see that people were producing beautiful frames but there was a hard edge to things, that was not the result of the photographs aesthetic, but more a result of the technical side of the process.

Looking at my contemporary greats say the stellar David Bailey, I made the mistake of thinking that their aesthetic was somehow wrong, when compared say to my heroes such as Edward Steichen! I was totally off the mark of course. As always the aesthetic judgements we make are more emotional and personal than any kind of academic or analytical overview. I was wrong in every way. My kicking against the trends though led me to experiment and search out the material that had become redundant. Wrong as I may have been; I mean after all Avedon’s work was heart-achingly beautiful, as was Bailey’s or any number of the master photographers of the period; the path I took led me to my own style, my own eye.

So I built pinhole cameras, with paper negatives loaded, that needed ten minute exposures, and hours of testing before I could work out the technical details needed to produce actual photographs with them. My shoebox pinhole led me to understand the value of that second most important component of photography – Time. It really was the best demonstration of the role that time plays in the creation of the photographic image. It clarified so many things for me in my excitement and enthusiasm and youthful rage at fashions of my time. This drive fuelled my work, it sent me in search of material and techniques that were no longer in use or in fashion.

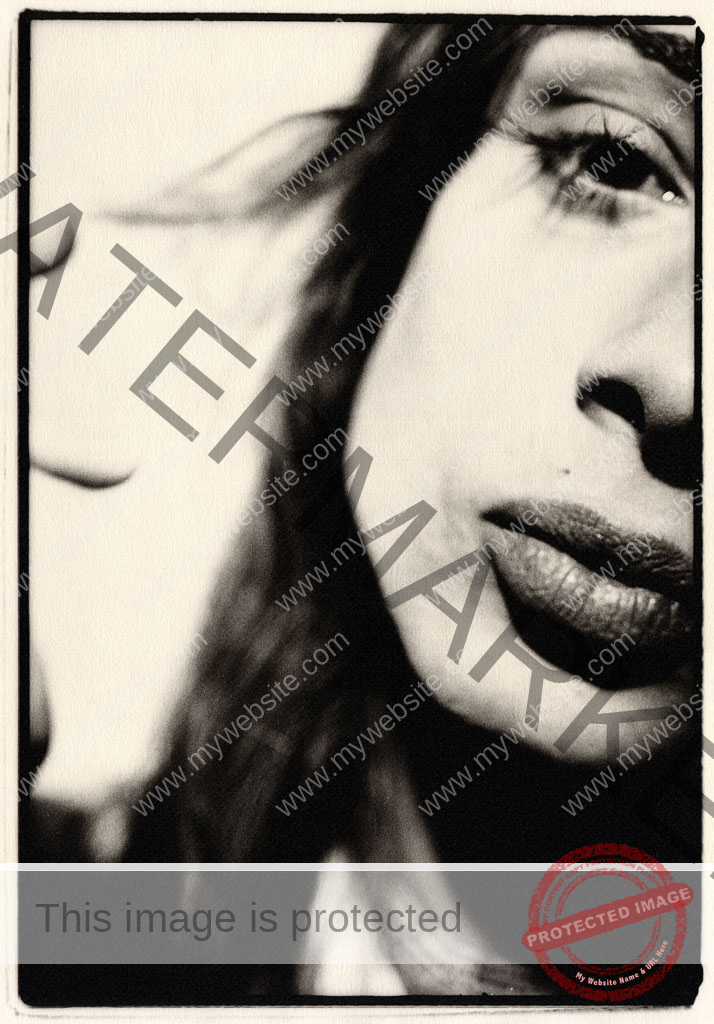

I was massively attracted to the feel of the photographs of the early Twentieth Century. I wanted to work out how they got those rich out of focus images, with isolated areas of sharpness, that other worldly quality of light. I wanted to know it and make it mine.

To that end I experimented. I hunted out and finally found supplies of Agfa Portriga and Record Rapid bromide papers, heavily coated and graded on Baryta papers, with their sheen that depended on how you processed and finished them. From the same paper you could get a high gloss or a silky matt simply by the way you washed and dried your prints. I found films that it seemed no one was using. The go to films at this time were HP5 from Ilford or Kodak’s crazy paved Tri-X, rated at 400 ASA from the factory, but often pushed to 1600 or even 3200, shot at high contrast and then printed on grade 5 or 6 or even higher contrasts. Photos were black and white for real. No greys to be seen anywhere. So I went for films that were rated at 25 ASA, pulled to even lower ratings, then processed in slow high acutance chemicals, my favourite was Ilford Perceptol diluted to even lower proportions and extended development times to get all the greys from shadows to highlights. I managed in my experiments to achieve curves on the densitometer of 1 to 3 ratio, which my tutors assured me were mythical ideals. I was obsessed. And I produced images that got that whole feel. I used old rail cameras or bought old lenses, working in lower light with low ASA ratings with my lens opened up to maximum aperture to throw most of the image out of focus.

Anyway I don’t wanna get myself too excited now. Suffice to say I did everything I could to turn back the clock without actually falling out of my own time completely.

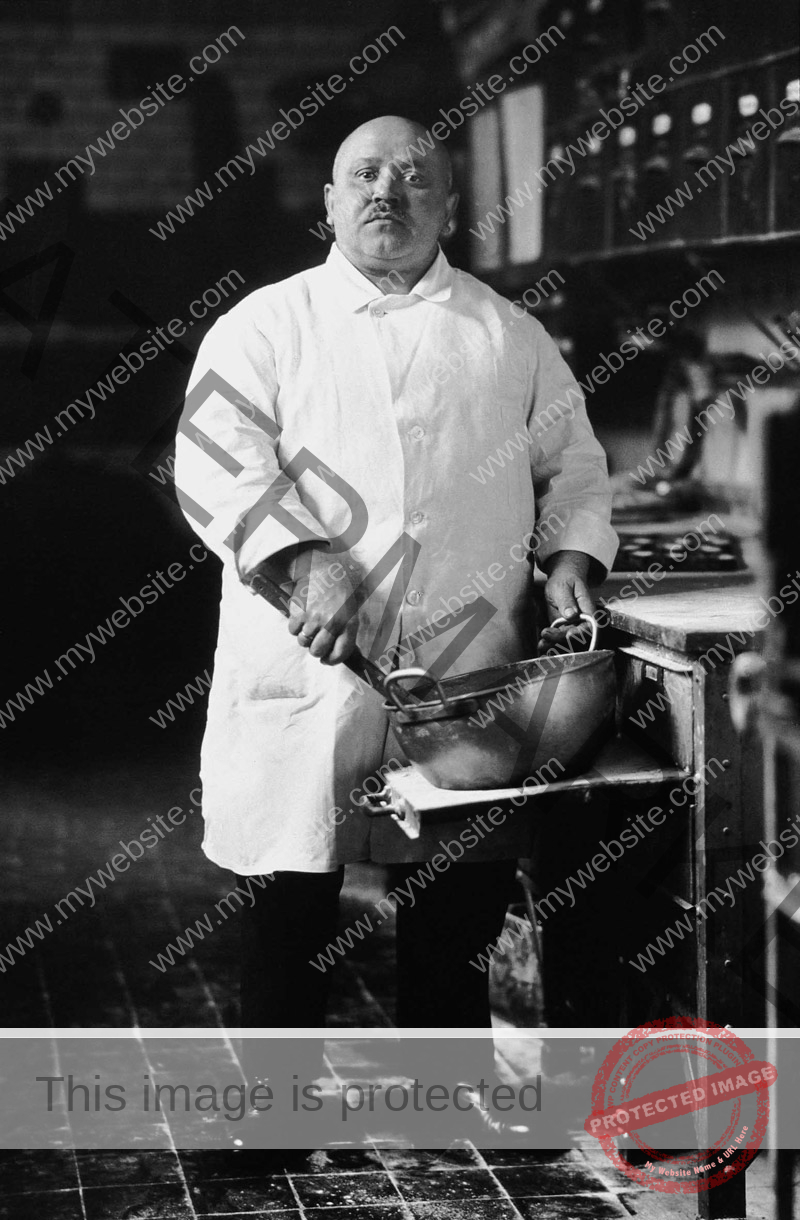

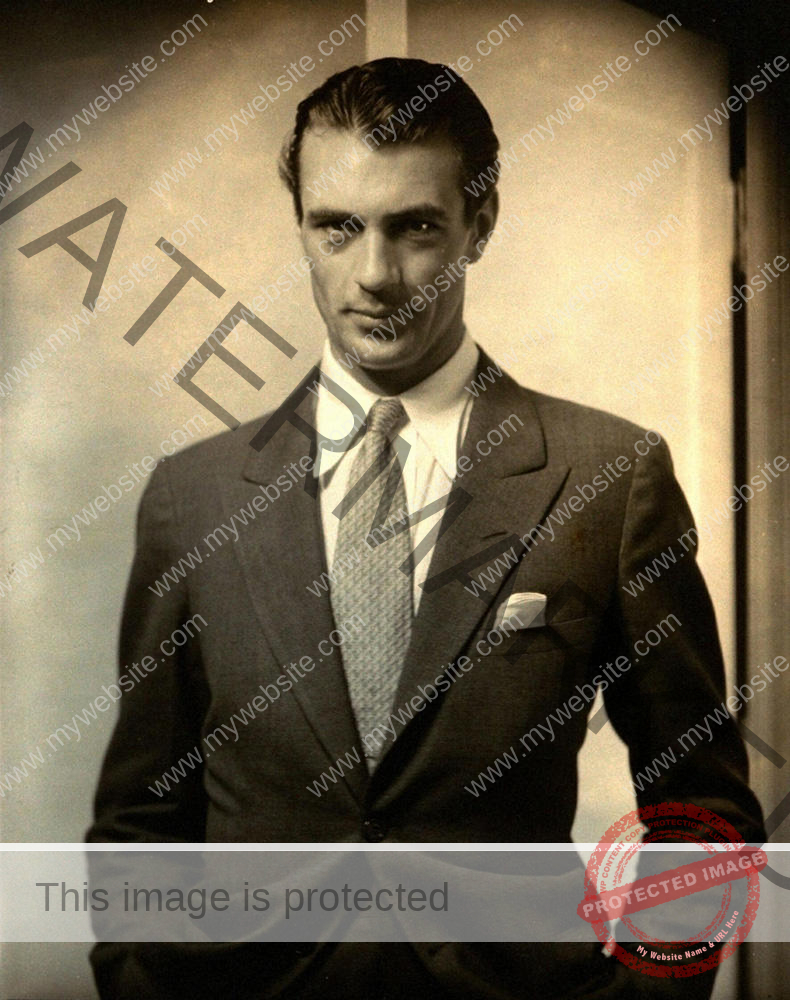

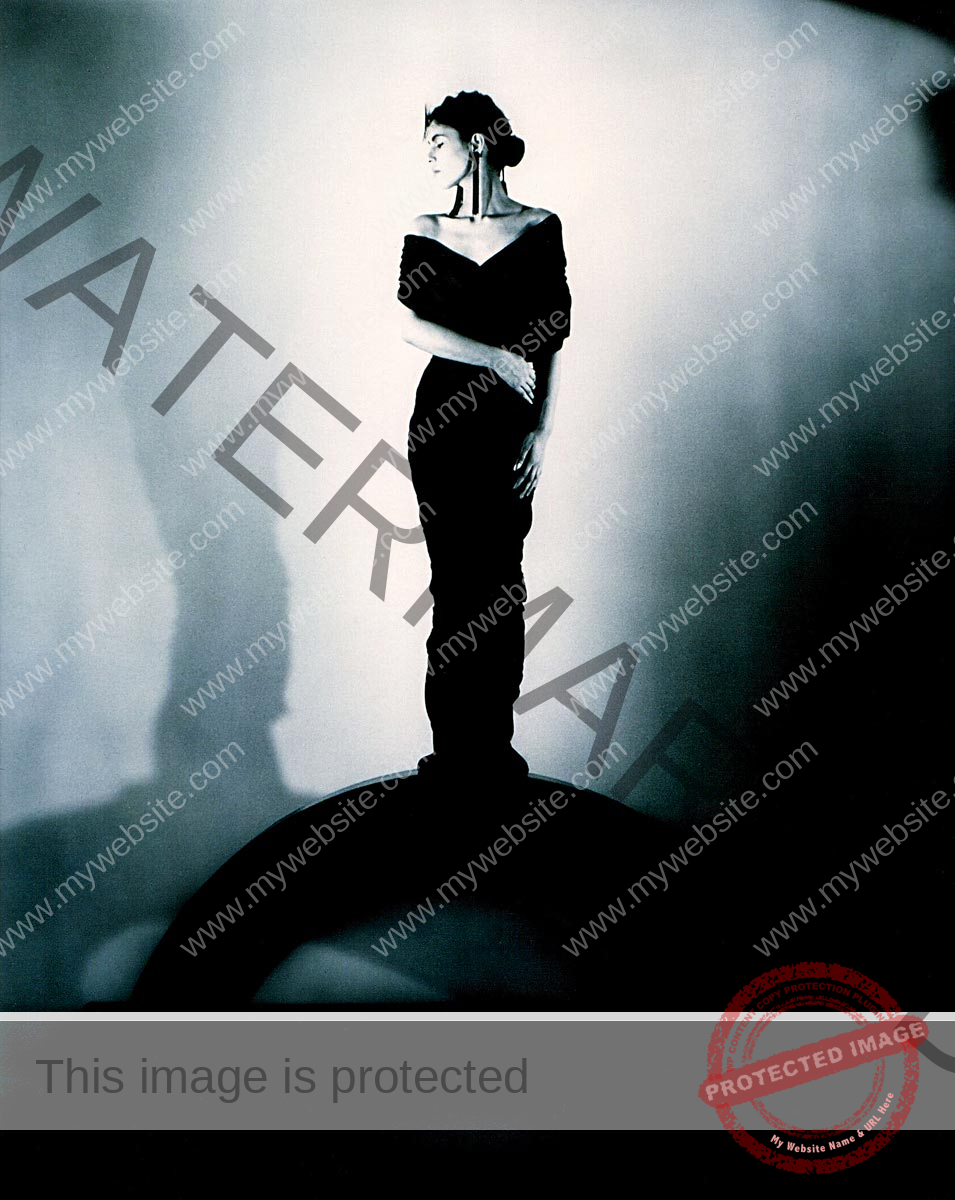

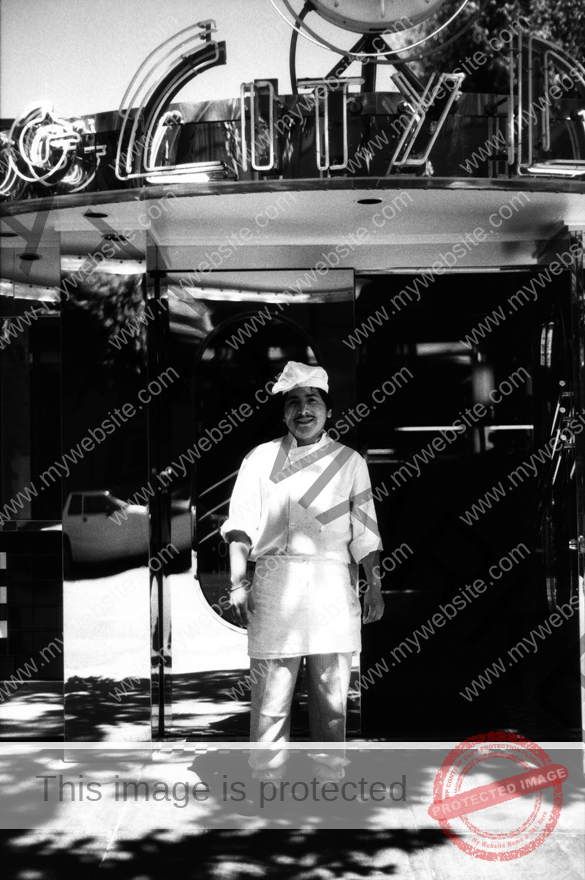

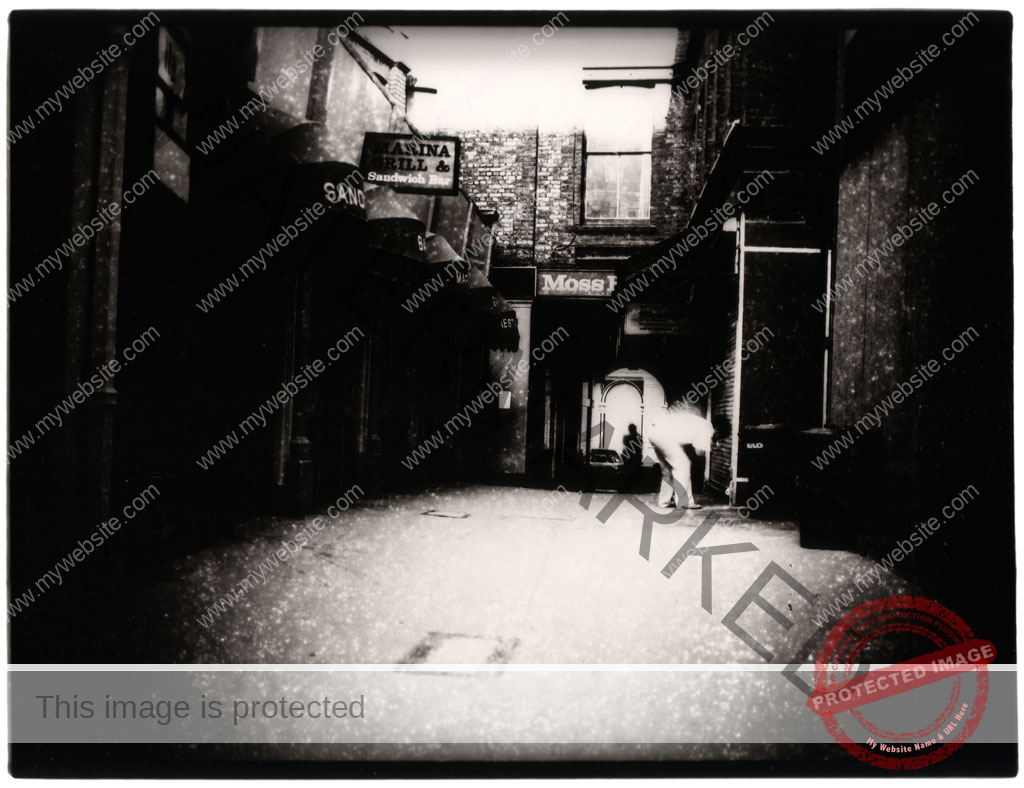

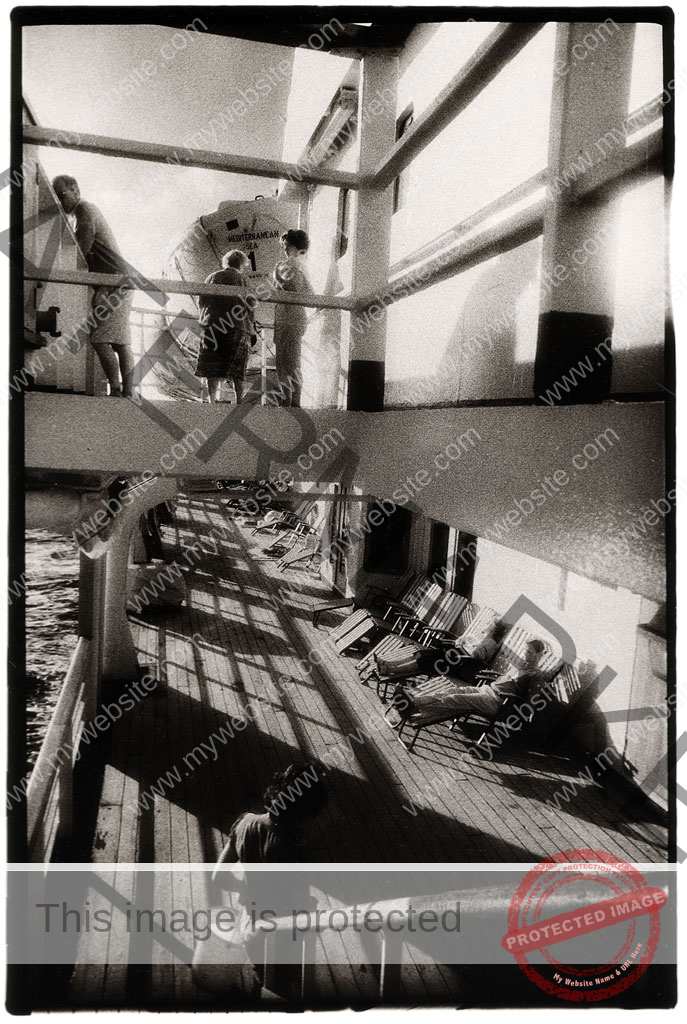

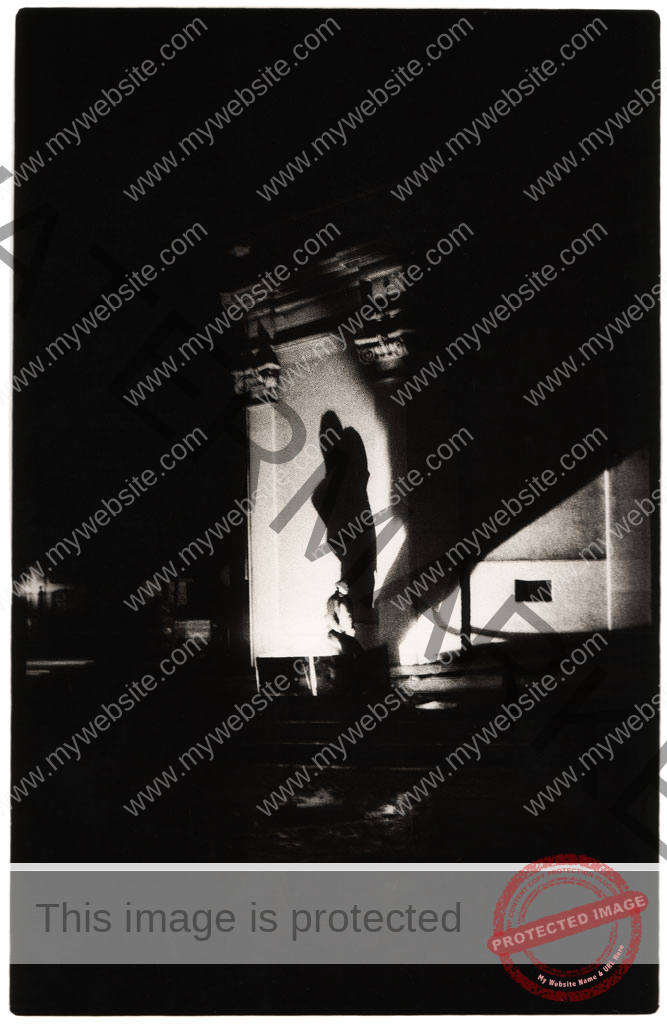

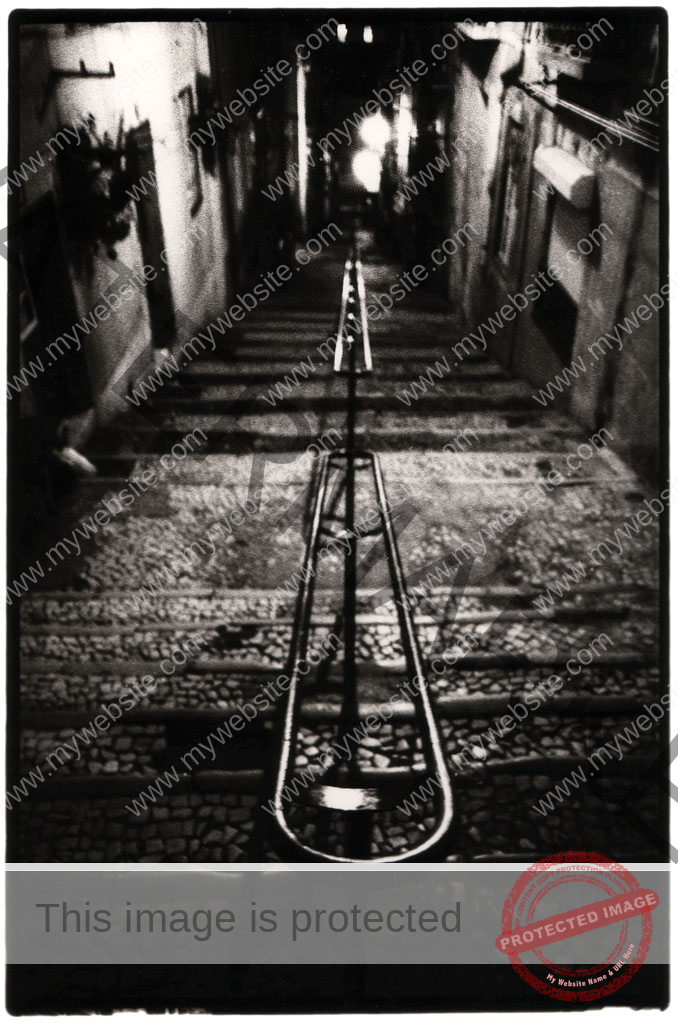

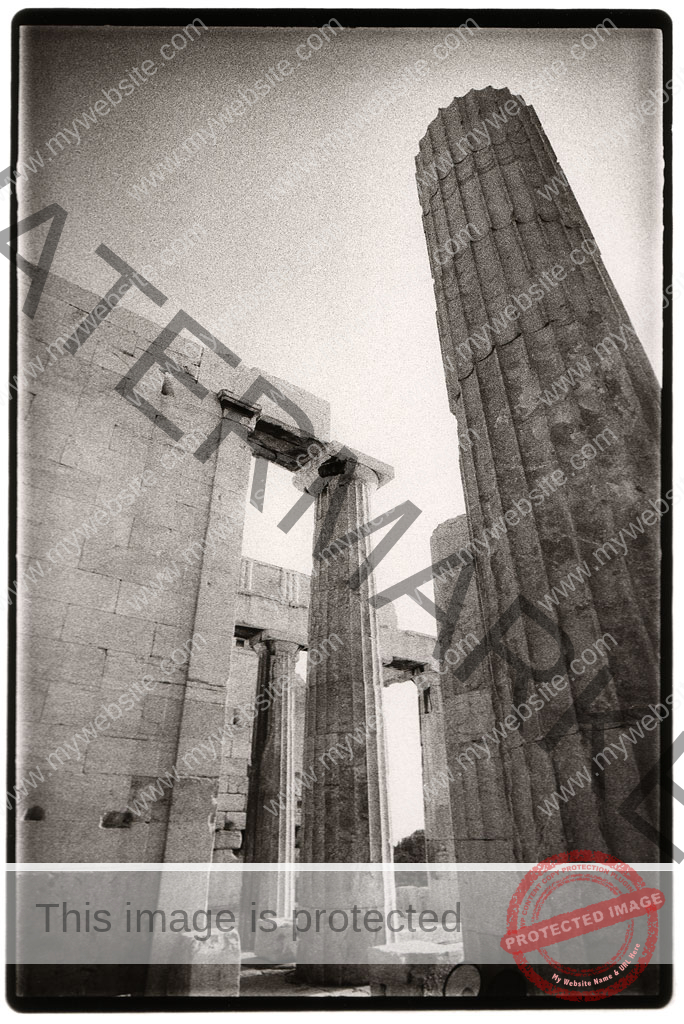

Above: From the series “Invisible Cities” © 1989-2012 Vishy Moghan (Mamiya 645)

I developed whole chemical armouries to support this new habit. Collected old outdated films and papers, worked day and night in my darkroom, tested and wrote technical papers on every aspect of darkroom technique, became something of a chemical wizard to keep on supporting my habit. I was in short a photographic hop-head!

At this point you may be asking yourself “OK fine but what’s the point?” The point is this: that one thing, one real luxury that we can not afford to deny photographs is time. Time really is the essence of a finished photograph. There are no short-cuts, no quick fixes, no magic buttons. All the technology in the world can not produce the depth of atmosphere and texture that a well worked, well processed, well considered photograph can give you. Time is what produces photographs that are timeless. And believe me it means working on your technique and on your deep knowledge of the photographic process and of learning the history intimately. Without it we’re doomed to tawdriness and shallowness of vision. Without it the quintessential art of the Twentieth Century is lost. Just look how people, even young people who maybe have never held an old print in their hands still hanker after the feel of those old photographs. Why else would there be such a thing as “Instagram” or “Retrica”? It amazes me that as early as the 90’s, when I showed my folio people were asking me if I had Photoshopped the images!!!! And when I said “No this is camera, studio and darkroom technique”, they looked at me as if I was some kind of alien.

P.S. The influences that I gathered in my early days really came through in one key project in 1993. This was my legendary road trip in the U.S. which became a book. The section “Route ’93” is dedicated to that project. Thank you Messrs Sander, Frank, Steichen, Lartigue, Stieglitz, Adams et al.